Amebiasis

Amebic dysentery; Intestinal amebiasis; Amebic colitis; Diarrhea - amebiasis

Amebiasis is an infection of the intestines. It is caused by the microscopic parasite Entamoeba histolytica.

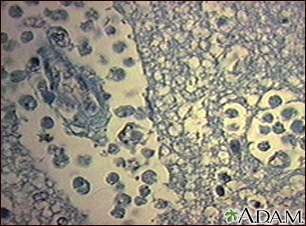

Amebiasis, normally an infection of the intestinal tract, may spread and infect other organs such as the liver or brain. Infection of the brain can be fatal. In this slide, ameba are shown in a sample of brain tissue. Ameba represent a serious infection in immunocompromised individuals. (Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

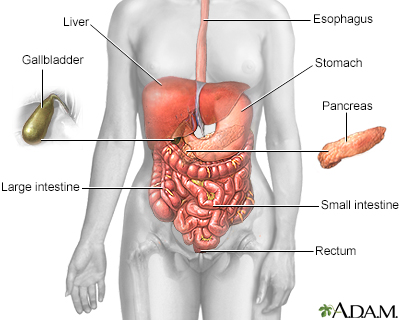

The esophagus, stomach, large and small intestine, aided by the liver, gallbladder and pancreas convert the nutritive components of food into energy and break down the non-nutritive components into waste to be excreted.

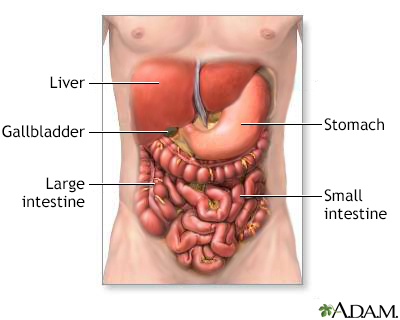

The digestive system organs in the abdominal cavity include the liver, gallbladder, stomach, small intestine and large intestine.

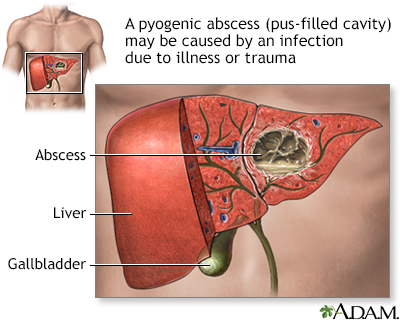

A liver abscess can develop from several different sources, including a blood infection, an abdominal infection, or an abdominal injury which has been become infected. The most common infecting bacteria include E coli, enterococcus, staphylococcus, and streptococcus. Treatment is usually a combination of drainage and prolonged antibiotic therapy.

Causes

E histolytica can live in the large intestine (colon) without causing damage to the intestine. In some cases, it invades the colon wall, causing colitis, acute dysentery, or long-term (chronic) diarrhea. The infection can also spread through the bloodstream to the liver. In rare cases, it can spread to the lungs, brain, or other organs.

This condition occurs worldwide. It is most common in tropical areas that have crowded living conditions and poor sanitation. Africa, Mexico, parts of South America, and India have major health problems due to this condition.

The parasite may spread:

- Through food or water contaminated with stool

- Through fertilizer made of human waste

- From person to person, particularly by contact with the mouth or rectal area of an infected person

Risk factors for severe amebiasis include:

- Alcohol use

- Cancer

- Malnutrition

- Older or younger age

- Pregnancy

- Recent travel to a tropical region

- Use of any corticosteroid medicine to suppress the immune system

In the United States, amebiasis is most common among those who live in institutions or people who have traveled to an area where amebiasis is common.

Symptoms

Most people with this infection do not have symptoms. If symptoms occur, they are seen 7 to 28 days after being exposed to the parasite.

Mild symptoms may include:

- Abdominal cramps

- Diarrhea: passage of 3 to 8 semiformed stools per day, or passage of soft stools with mucus and occasional blood

- Fatigue

- Excessive gas

- Rectal pain while having a bowel movement

- A sensation of needing to have a bowel movement even when the rectum is empty (tenesmus)

- Unintentional weight loss

Severe symptoms may include:

- Abdominal tenderness

- Bloody stools, including passage of liquid stools with streaks of blood, passage of 10 to 20 stools per day

- Fever

- Vomiting

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam. You will be asked about your medical history, especially if you have recently traveled overseas.

Examination of the abdomen may show liver enlargement or tenderness in the abdomen (typically in the right upper quadrant).

Tests that may be ordered include:

- Blood test for amebiasis

- Examination of the inside of the lower large bowel (sigmoidoscopy)

- Stool test

- Microscope examination of stool samples, usually with multiple samples over several days

Treatment

Treatment depends on how severe the infection is. Usually, antibiotics are prescribed.

If you are vomiting, you may be given medicines through a vein (intravenously) until you can take them by mouth. Medicines to stop diarrhea are usually not prescribed because they can make the condition worse.

After antibiotic treatment, your stool will likely be rechecked to make sure the infection has been cleared.

Outlook (Prognosis)

The outcome is usually good with treatment. Usually, the illness lasts about 2 weeks, but it can come back if you do not get treated.

Possible Complications

Complications of amebiasis may include:

- Amebic liver abscess (collection of parasites and pus in the liver)

- Medicine side effects, including nausea

- Spread of the parasite through the blood to the liver, lungs, brain, or other organs

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have diarrhea that does not go away or gets worse.

Prevention

When traveling in countries where sanitation is poor, drink purified or boiled water. Do not eat uncooked vegetables or unpeeled fruit. Wash your hands after using the bathroom and before eating.

References

Petri WA, Haque R, Moonah SN. Entamoeba species, including amebic colitis and liver abscess. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 272.

Salvana EMT, Salata RA. Amebiasis. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 327.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 8/29/2024

Reviewed by: Jatin M. Vyas, MD, PhD, Professor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Associate in Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.