Optic neuritis

Retro-bulbar neuritis; Multiple sclerosis - optic neuritis; Optic nerve - optic neuritis

The optic nerve carries images of what the eye sees to the brain. When this nerve become swollen or inflamed, it is called optic neuritis. It may cause sudden, reduced vision in the affected eye.

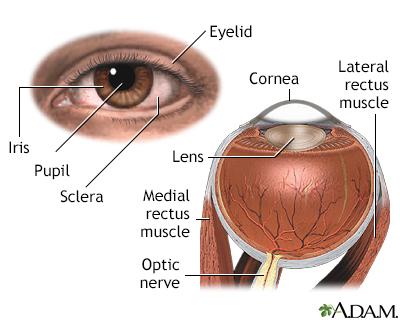

The cornea allows light to enter the eye. As light passes through the eye the iris changes shape by expanding and letting more light through or constricting and letting less light through to change pupil size. The lens then changes shape to allow the accurate focusing of light on the retina. Light excites photoreceptors that eventually, through a chemical process, transmit nerve signals through the optic nerve to the brain. The brain processes these nerve impulses into sight.

Causes

The exact cause of optic neuritis is unknown.

The optic nerve carries visual information from your eye to the brain. The nerve can swell when it becomes inflamed. The swelling can damage nerve fibers. This can cause short or long-term loss of vision.

Conditions that have been linked with optic neuritis include:

- Autoimmune diseases, including lupus, sarcoidosis, and Behçet disease

- Cryptococcosis, a fungal infection

- Bacterial infections, including tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme disease, and meningitis

- Viral infections, including viral encephalitis, measles, rubella, chickenpox, herpes zoster, mumps, and mononucleosis

- Respiratory infections, including mycoplasma pneumonia and other common upper respiratory tract infections

- Multiple sclerosis

Symptoms

Symptoms may include:

- Loss of vision in one eye over an hour or a few hours

- Changes in the way the pupil reacts to bright light

- Loss of color vision

- Pain when you move your eye

Exams and Tests

A complete medical exam can help rule out related diseases. Tests may include:

- Color vision testing

- MRI of the brain, including special images of the optic nerve

- Visual acuity testing

- Visual field testing

- Examination of the optic disc using indirect ophthalmoscopy

Treatment

Vision often returns to normal within 2 to 3 weeks with no treatment.

Corticosteroids given through a vein (IV) or taken by mouth (oral) may speed up recovery. However, the final vision is no better with steroids than without. Oral steroids may actually increase the chance of recurrence.

If tests suggest that there is also multiple sclerosis, other types of treatment may be helpful.

Further tests may be needed to try to find the cause of the neuritis. If there is a condition causing the problem, it may be able to be treated.

Outlook (Prognosis)

When optic neuritis occurs without other diseases, there is a better prognosis. An MRI is an important test because it can help predict if multiple sclerosis or other similar autoimmune diseases are present or may develop.

Optic neuritis caused by multiple sclerosis or other autoimmune diseases has a poorer outlook. However, vision in the affected eye may still return to normal.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Body-wide side effects from corticosteroids

- Vision loss

Some people who have an episode of optic neuritis will develop nerve problems in other places in the body or develop multiple sclerosis.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your health care provider right away if you have a sudden loss of vision in one eye, especially if you have eye pain.

If you have been diagnosed with optic neuritis, contact your provider if:

- Your vision decreases.

- The pain in the eye gets worse.

- Your symptoms do not improve within 2 to 3 weeks.

References

Bennett JL. Optic neuritis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25(5):1236-1264. PMID: 31584536

Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis and demyelinating conditions of the central nervous system. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 380.

Filipi M, Jack S. Interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability update. Int JMS Care. 2020;22(4):165-172. PMID: 32863784

Moss HE, Balcer LJ. Inflammatory optic neuropathies and neuroretinitis. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 9.7.

Thurtell MJ, Prasad S, Tomsak RL. Neuro-ophthalmology: afferent visual system. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 16.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 1/29/2024

Reviewed by: Audrey Tai, DO, MS, Athena Eye Care, Mission Viejo, CA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.