Central venous catheters - ports

Central venous catheter - subcutaneous; Port-a-Cath; InfusaPort; PasPort; Subclavian port; Medi - port; Central venous line - port

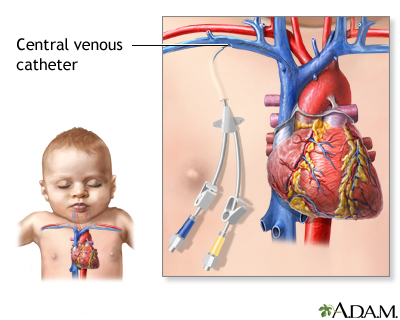

A central venous catheter is a thin tube that goes into a vein in your arm or chest and ends at the right side of your heart (right atrium).

If the catheter is in your chest, sometimes it is attached to a device called a port that will be under your skin. The port and catheter are put in place in a minor surgery.

The catheter helps carry nutrients and medicine into your body. It can also be used to take blood when you need to have blood tests. Having a port attached to your catheter will cause less wear and tear on your veins than just having the catheter.

A central venous catheter is a long, soft plastic tube (usually made of silicone) that is placed via a small cut in the neck, chest, or groin into a large vein in the chest to allow IV fluids and medications to be given over an extended period of time.

What is the Purpose of a Central Venous Catheter and Port?

Central venous catheters with ports are used when you need treatment over a long period of time. For example, you may need:

- Antibiotics or other medicines for weeks to months

- Extra nutrition because your bowels are not working correctly

Or you may be receiving:

- Kidney dialysis several times a week

- Cancer medicines often

Your health care provider will talk with you about other methods for receiving medicine and fluids into a vein and will help you decide which one is best for you.

Placing the Port

A port is placed under your skin in a minor surgery. Most ports are placed in the chest. But they may also be placed in the arm.

- You may be placed into a deep sleep so you do not feel pain during surgery.

- You may stay awake and receive medicines to help you relax and numb the area so you do not feel pain.

You can go home after your port is placed.

- You will be able to feel and see a quarter-sized bump under your skin where your port is.

- You may be a little sore for a few days after surgery.

- Once you have healed, your port should not hurt.

Taking Care of and Using Your Port

Your port has 3 parts.

- Portal or reservoir. A pouch made of hard metal or plastic.

- Silicone top. Where a needle is inserted into the portal.

- Tube or catheter. Carries medicine or blood from the portal to a large vein and into the heart.

To get medicine or nutrition through your port, a trained provider will stick a special needle through your skin and the silicone top and into the portal. A numbing cream can be used on your skin to decrease the pain of the needle stick.

- Your port may be used in your home, in a clinic, or in the hospital.

- A sterile dressing (bandage) will be placed around your port when it is used to help prevent infection.

When your port is not being used, you can bathe or swim, as long as your provider says you are ready for activity. Check with your provider if you plan to do any contact sports, such as soccer and football.

Nothing will stick out of your skin when your port is not being used. This decreases your chance of infection in or around your port.

About once a month, you will need to have your port flushed to help prevent clots. To do this, your provider will use a special solution.

Ports can be used for a long time. When you no longer need your port, your provider will remove it.

When to Call the Doctor

Tell your provider right away if you notice any signs of infection, such as:

- Your port seems to have moved.

- Your port site is red, or there are red streaks around the site.

- Your port site is swollen or warm.

- Yellow or green drainage is coming from your port site.

- You have pain or discomfort at the site.

- You have a fever over 100.5°F (38.0°C).

- Your port cannot be accessed with the special needle.

References

Dixon RG. Subcutaneous ports. In: Mauro MA, Murphy KPJ, Thomson KR, Venbrux AC, Morgan RA, eds. Image-Guided Interventions. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 85.

James D. Central venous catheter insertion. In: Fowler GC, ed. Pfenninger and Fowler's Procedures for Primary Care. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 228.

Witt SH, Carr CM, Krywko DM. Indwelling vascular access devices: emergency access and management. In: Roberts JR, Custalow CB, Thomsen TW, eds. Roberts and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 24.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 4/9/2024

Reviewed by: Frank D. Brodkey, MD, FCCM, Associate Professor, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.