Kidney stones - lithotripsy - discharge

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy - discharge; Shock wave lithotripsy - discharge; Laser lithotripsy - discharge; Percutaneous lithotripsy - discharge; Endoscopic lithotripsy - discharge; ESWL - discharge; Renal calculi - lithotripsy; Nephrolithiasis - lithotripsy; Renal colic - lithotripsy

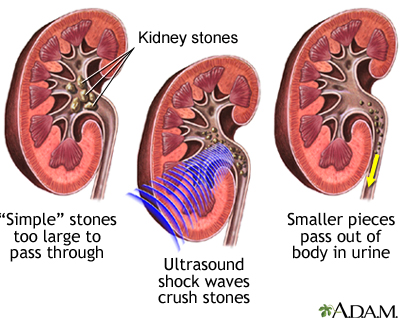

A kidney stone is a small solid mass made up of tiny crystals. You had a medical procedure called lithotripsy to break up the kidney stones. This article gives you advice on what to expect and how to take care of yourself after the procedure.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is a procedure used to shatter simple stones in the kidney or upper urinary tract. Ultrasonic waves are passed through the body until they strike the dense stones. Pulses of sonic waves pulverize the stones, which are then more easily passed through the ureter and out of the body in the urine.

When You're in the Hospital

You had lithotripsy, a medical procedure that uses high frequency sound (shock) waves or a laser to break up stones in your kidney, bladder, or ureter (the tube that carries urine from your kidneys to your bladder). The sound waves or laser beam breaks the stones into tiny pieces.

What to Expect at Home

It is normal to have a small amount of blood in your urine for a few days to a few weeks after this procedure.

You may have pain and nausea when the stone pieces pass. This can happen soon after treatment and may last for 4 to 8 weeks.

You may have some bruising on your back or side where the stone was treated if sound waves were used. You may also have some pain over the treatment area.

Self-care

Have someone drive you home from the hospital. Rest when you get home. Most people can go back to their regular daily activities 1 or 2 days after this procedure.

Drink a lot of water in the weeks after treatment. This helps pass any pieces of stone that still remain. Your health care provider may give you a medicine called an alpha blocker to make it easier to pass the pieces of stone.

Learn how to prevent your kidney stones from coming back.

Take the pain medicine your provider has told you to take and drink a lot of water if you have pain. You may need to take antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medicines for a few days.

You will probably be asked to strain your urine at home to look for stones. Your provider will tell you how to do this. Any stones you find can be sent to a medical lab to be examined.

You will need to see your provider for a follow-up appointment in the weeks after your lithotripsy.

You may have a nephrostomy drainage tube or an indwelling stent. You will be taught how to take care of it.

When to Call the Doctor

Contact your provider if you have:

References

Bushinsky DA. Nephrolithiasis. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 111.

Matlaga BR, Krambeck AE. Surgical management for upper urinary tract calculi. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 94.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 9/2/2024

Reviewed by: Kelly L. Stratton, MD, FACS, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.