Absence seizure

Seizure - petit mal; Seizure - absence; Petit mal seizure; Epilepsy - absence seizure; Non-motor generalized seizure

An absence seizure is the term for a type of seizure involving staring spells. This type of seizure is a brief (usually less than 15 seconds) change in awareness due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain.

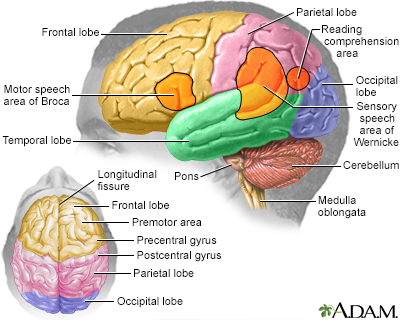

The major areas of the brain have one or more specific functions.

Causes

Seizures result from overactivity in the brain. Absence seizures occur most often in people under age 20, usually in children ages 4 to 12 years.

In some cases, the seizures are triggered by flashing lights or when the person breathes faster and more deeply than usual (hyperventilates).

They may also occur with other types of seizures, such as bilateral tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal seizures), twitches or jerks (myoclonus), or sudden loss of muscle strength (atonic seizures).

Symptoms

Most absence seizures last only a few seconds. They often involve staring episodes. The episodes may:

- Occur many times a day

- Occur for weeks to months before being noticed

- Interfere with school and learning

- Be mistaken for lack of attention, daydreaming or other misbehavior

Unexplained difficulties in school and learning difficulties may be the first sign of absence seizures.

During the seizure, the person may:

- Stop walking and start again a few seconds later

- Stop talking in mid-sentence and start again a few seconds later

The person usually does not fall during the seizure.

Right after the seizure, the person is usually:

- Wide awake

- Thinking clearly

- Unaware of the seizure

Specific symptoms of typical absence seizures may include:

- Changes in muscle activity, such as no movement, hand fumbling, fluttering eyelids, lip smacking, chewing

- Changes in alertness (consciousness), such as staring episodes, lack of awareness of surroundings, sudden halt in movement, talking, and other awake activities

Some absence seizures begin slower and last longer. These are called atypical absence seizures. Symptoms are similar to regular absence seizures, but muscle activity changes may be more noticeable.

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam. This will include a detailed look at the brain and nervous system.

An electroencephalogram (EEG) will be done to check the electrical activity in the brain. People with seizures often have abnormal electrical activity seen on this test. In some cases, the test shows the area in the brain where the seizures start. The brain may appear normal after a seizure or between seizures.

Blood and urine tests may also be ordered to check for other health problems that may be causing the seizures.

Head CT or MRI scan may be done to find the cause and location of the problem in the brain.

Treatment

References

Abou-Khalil BW, Gallagher MJ, Macdonald RL. Epilepsies. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 100.

Kanner AM, Ashman E, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs I: Treatment of new-onset epilepsy: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2018;91(2):74-81. PMID: 29898971

Mikati MA, Tchapyjnikov D, Rathke KM. Seizures in childhood. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 633.

Wiebe S. The epilepsies. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 372.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 3/31/2024

Reviewed by: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.