Empty sella syndrome

Pituitary - empty sella syndrome; Partial empty sella

Empty sella syndrome is a condition in which the pituitary gland shrinks or becomes flattened.

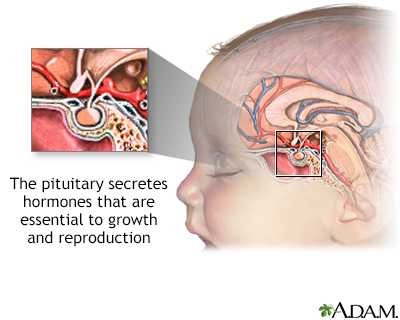

The pituitary is a gland attached to the base of the brain. The pituitary secretes hormones that regulate the body's balance of many hormones controlling growth, development, and metabolism of the body.

Causes

The pituitary is a small gland located just underneath the brain. It is attached to the bottom of the brain by the pituitary stalk. The pituitary sits protected inside a saddle-like bony compartment in the base of the skull. This compartment is called the sella turcica, but often just called the sella.

When the pituitary gland shrinks or becomes flattened, it cannot be seen on an MRI scan. This makes the area of the pituitary gland look like an "empty sella." But the sella is not actually empty. It is often filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF is fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. With empty sella syndrome, CSF has leaked into the sella turcica, putting pressure on the pituitary. This causes the gland to shrink or flatten.

Primary empty sella syndrome occurs when one of the layers (arachnoid) covering the outside of the brain bulges down into the sella and presses on the pituitary.

Secondary empty sella syndrome occurs when the sella is empty because the pituitary gland has been damaged by:

- A tumor

- Radiation therapy

- Surgery

- Trauma

Empty sella syndrome may be seen in a condition called pseudotumor cerebri, which mainly affects young, obese women and causes the CSF to be under higher pressure.

The pituitary gland makes several hormones that control other glands and hormones in the body, including:

- Adrenal glands

- Liver hormone related to growth (insulin-like growth factor-1)

- Ovaries

- Testicles

- Thyroid

A problem with the pituitary gland can lead to problems with any of the above glands and abnormal hormone levels of these glands.

Symptoms

Often, there are no symptoms or loss of pituitary function.

If there are symptoms, they may include any of the following:

- Erection problems

- Headaches

- Irregular or absent menstruation

- Decreased or no desire for sex (low libido)

- Fatigue, low energy

- Nipple discharge

Exams and Tests

Primary empty sella syndrome is most often discovered during an MRI or CT scan of the head and brain. Pituitary function is usually normal.

Your health care provider may order tests to check if the pituitary gland is working normally.

Sometimes, tests for high pressure in the brain will be done, such as:

- Examination of the retina by an ophthalmologist

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap)

Treatment

For primary empty sella syndrome:

- No treatment is needed if pituitary function is normal.

- Medicines may be prescribed to treat any abnormal hormone levels.

For secondary empty sella syndrome, treatment involves replacing the hormones that are missing.

In some cases, surgery is needed to repair the sella to prevent CSF from leaking into the nose and sinuses.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Primary empty sella syndrome does not cause health problems, and it does not affect life expectancy.

Possible Complications

Complications of primary empty sella syndrome include a slightly higher than normal level of prolactin. This is a hormone made by the pituitary gland. Prolactin stimulates breast development and milk production in women.

Complications of secondary empty sella syndrome are related to the cause of pituitary gland disease or to the effects of too little pituitary hormone (hypopituitarism).

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you develop symptoms of abnormal pituitary function, such as menstrual cycle problems or impotence.

References

Bashari WA, Gillett D, MacFarlane J, Scoffings D, Gurnell M. Pituitary imaging. In: Melmed S, ed. The Pituitary. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 23.

Johannsson G, Ragnarsson O. Hypopituitarism including growth hormone deficiency. In: Robertson RP, ed. DeGroot's Endocrinology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 5.

Kaiser U, Ho K. Pituitary physiology and diagnostic evaluation. In: Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB, Koenig RJ, Rosen CJ, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 8.

Weiss RE. Anterior pituitary. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 205.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 5/12/2023

Reviewed by: Sandeep K. Dhaliwal, MD, board-certified in Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism, Springfield, VA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.