Esophageal perforation

Perforation of the esophagus; Boerhaave syndrome

An esophageal perforation is a hole in the esophagus. The esophagus is the tube food passes through as it goes from the mouth to the stomach.

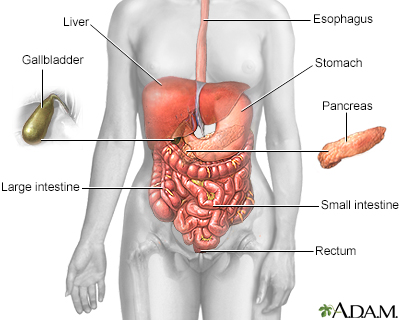

The esophagus, stomach, large and small intestine, aided by the liver, gallbladder and pancreas convert the nutritive components of food into energy and break down the non-nutritive components into waste to be excreted.

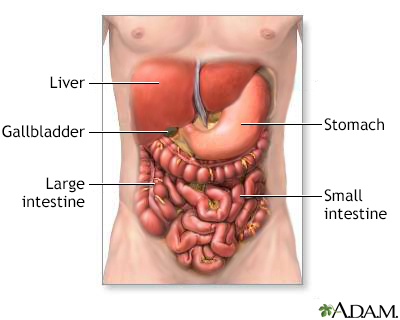

The digestive system organs in the abdominal cavity include the liver, gallbladder, stomach, small intestine and large intestine.

Causes

When there is a hole in the esophagus, the contents of the esophagus can pass into the surrounding area in the chest (mediastinum). This often results in infection of the mediastinum (mediastinitis).

The most common cause of an esophageal perforation is injury during a medical procedure. However, the use of flexible instruments has made this problem uncommon.

The esophagus may also become perforated as the result of:

- A tumor

- Gastric reflux with ulceration

- Previous surgery on the esophagus

- Swallowing a foreign object or caustic chemicals, such as household cleaners, disk batteries, and battery acid

- Trauma or injury to the chest and esophagus

- Violent vomiting (Boerhaave syndrome)

Less common causes include injuries to the esophagus area (blunt trauma) and injury to the esophagus during surgery of another organ near the esophagus.

Symptoms

The main symptom is pain when the problem first occurs.

A perforation in the middle or lower most part of the esophagus may cause:

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will look for:

- Fast breathing

- Fever

- Low blood pressure

- Rapid heart rate

- Neck pain or stiffness

- Air bubbles underneath the skin if the perforation is in the top part of the esophagus

You may have a chest x-ray to look for:

- Air in the soft tissues of the chest

- Fluid that has leaked from the esophagus into the space around the lungs

- Collapsed lung -- X-rays taken after you drink a non-harmful dye can help pinpoint the location of the perforation

You may also have a chest CT scan to look for an abscess in the chest or esophageal cancer.

Treatment

You may need surgery. Surgery will depend on the location and size of the perforation. If surgery is needed, it is best done within 24 hours.

Treatment may include:

- Fluids given through a vein (IV)

- IV antibiotics to prevent or treat infection

- Draining of fluid around the lungs with a chest tube

- Mediastinoscopy to remove fluid that has collected in the area behind the breastbone and between the lungs (mediastinum)

A stent may be placed in the esophagus if only a small amount of fluid has leaked. This may help avoid surgery.

A perforation in the uppermost (neck region) part of the esophagus may heal by itself if you do not eat or drink for a period of time. In this case, you will need a stomach feeding tube or another way to get nutrients.

Surgery is often needed to repair a perforation in the middle or bottom portions of the esophagus. Depending on the extent of the problem, the leak may be treated by simple repair or by removing the esophagus.

Outlook (Prognosis)

The condition can progress to shock, or even death, if untreated.

Outlook is good if the problem is found within 24 hours of it occurring. Most people survive when surgery is done within 24 hours. Survival rate goes down if you wait longer.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Permanent damage to the esophagus (narrowing or stricture)

- Abscess formation in and around the esophagus

- Infection in and around the lungs

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Tell your provider right away if you develop chest pain or trouble breathing when you are already in the hospital.

Go to the emergency room or call 911 or the local emergency number if:

- You have recently had surgery or a tube placed in the esophagus and you have chest pain, problems swallowing, or breathing.

- You have another reason to suspect that you may have esophageal perforation.

Prevention

These injuries, although uncommon, are hard to prevent.

References

Muñoz-Largacha JA, Donahue JM. Management of esophageal perforation. In: Cameron J, ed. Current Surgical Therapy. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:74-80.

Raja AS. Thoracic trauma. In: Walls RM, ed. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 37.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 10/30/2024

Reviewed by: Jenifer K. Lehrer, MD, Gastroenterologist, Philadelphia, PA. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.