Intrauterine growth restriction

Intrauterine growth retardation; IUGR; Pregnancy - IUGR

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) refers to the poor growth of a baby while in the mother's womb during pregnancy.

This is a normal fetal ultrasound performed at 19 weeks gestation. Many health care providers like to have fetal measurements to verify the size of the fetus and to look for any abnormalities. This ultrasound is of an abdominal measurement. It shows a cross-section of the abdomen, and the measurements are indicated by the cross hairs and dotted lines.

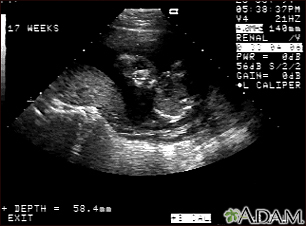

This is a normal fetal ultrasound performed at 17 weeks gestation. This is the type of image pregnant mothers may see on the ultrasound screen, or that the technician may print. It shows the head on the right, and the cross hair pointing to the left ankle. The left leg and arm are visible in the center of the screen.

This is a normal ultrasound of the fetus performed at 17 weeks gestation. The fetal face can be seen in the middle of the screen. The head is tilted left toward the placenta, which can be seen as a mound in the left of the ultrasound image. Both eyes are visible, and the area of white within the eye is the lens. Other facial features, such as the nose and mouth, are also visible.

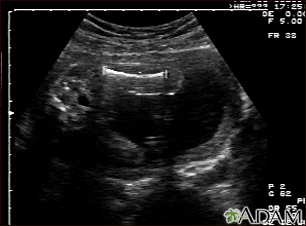

This is a normal ultrasound of the fetus performed at 19 weeks gestation. A clear view of the left femur (the large bone of the leg) can be seen in the middle, towards the top of the ultrasound screen.

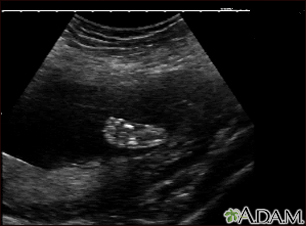

This is a normal ultrasound of a fetus at 19 weeks gestation. The right foot, including the developing bones, are clearly visible in the middle of the screen.

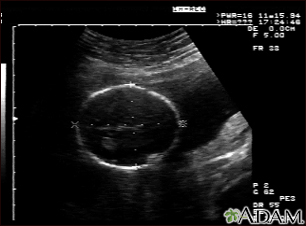

This is a normal fetal ultrasound performed at 19 weeks gestation. Many health care providers like to have fetal measurements to verify the size of the fetus and to look for any abnormalities. This ultrasound is of a head measurement, indicated by the cross hairs and dotted lines.

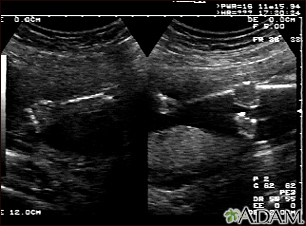

This is a normal fetal ultrasound performed at 19 weeks gestation. This is the type of spilt-screen display you might see during an ultrasound, or if the technician prints a copy of the ultrasound for you. This ultrasound shows both the left arm (seen in the left side of the display), and the lower extremities (seen in the right side of the display). The white areas of the arm or legs is developing bone.

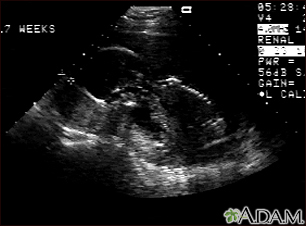

This is a normal fetal ultrasound performed at 17 weeks gestation. In the middle of the screen, the profile of the fetus is visible. The outline of the head can be seen in the left middle of the screen with the face down and the body in the fetal position extending to the lower right of the head. The outline of the spine can be seen on the right middle side of the screen.

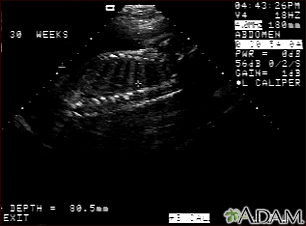

This is a normal fetal ultrasound performed at 30 weeks gestation. In the middle of the screen, a clear outline of the spine and ribs is visible. The cross hair is between two ribs just above the spine.

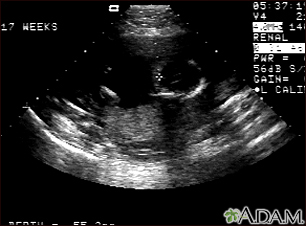

This is a normal fetal ultrasound performed at 17 weeks gestation. The development of the brain and nervous system begins early in fetal development. During an ultrasound, the technician usually looks for the presence of brain ventricles. Ventricles are spaces in the brain that are filled with fluid. In this early ultrasound, the ventricles can be seen as light lines extending through the skull, seen in the upper right side of the image. The cross hair is pointing to the front of the skull, and directly to the right, the lines of the ventricles are visible.

Causes

Many different things can lead to IUGR. An unborn baby may not get enough oxygen and nutrition from the placenta during pregnancy because of:

- Mother living at high altitude

- Multiple pregnancy, such as twins or triplets

- Placenta problems

- Preeclampsia or eclampsia

Problems at birth (congenital abnormalities) or chromosome problems are often associated with below-normal weight. Infections during pregnancy can also affect the weight of the developing baby. These include:

Risk factors in the mother that may contribute to IUGR include:

- Alcohol abuse

- Smoking

- Illicit drug use

- Clotting disorders

- High blood pressure or heart disease

- Diabetes

- Kidney disease

- Poor nutrition

- Thyroid disease

- Anemia

- Uterine malformations

- Multiple gestation

- Other chronic disease

If the mother is small, it may be normal for her baby to be small, and this is not due to IUGR.

Depending on the cause of IUGR, the developing baby may be small all over. Or, the baby's head may be normal size while the rest of the body is small.

Symptoms

A pregnant woman may feel that her baby is not as big as it should be. The measurement from the mother's pubic bone to the top of the uterus will be smaller than expected for the baby's gestational age. This measurement is called the uterine fundal height.

Exams and Tests

IUGR may be suspected if the size of the pregnant woman's uterus is small. The condition is most often confirmed by ultrasound.

More tests may be needed to screen for infection or genetic problems if IUGR is suspected.

Treatment

IUGR increases the risk that the baby will die inside the womb before birth. If your health care provider thinks you might have IUGR, you will be monitored closely. This will include regular pregnancy ultrasounds to measure the baby's growth, movements, blood flow, and fluid around the baby.

Nonstress testing will also be done. This involves listening to the baby's heart rate for a period of 20 to 30 minutes.

Depending on the results of these tests, your baby may need to be delivered early.

Outlook (Prognosis)

After delivery, the newborn's growth and development depends on the severity and cause of IUGR. Discuss the baby's outlook with your providers.

Possible Complications

IUGR increases the risk of pregnancy and newborn complications, depending on the cause. Babies whose growth is restricted often become more stressed during labor or C-section delivery.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider right away if you are pregnant and notice that your baby is moving less than usual.

After giving birth, contact your provider if your infant or child does not seem to be growing or developing normally.

Prevention

Following these guidelines will help prevent IUGR:

- Do not drink alcohol, smoke, or use recreational drugs.

- Eat healthy foods.

- Get regular prenatal care.

- If you have a chronic medical condition or you take prescribed medicines regularly, see your provider before you get pregnant. This can help reduce risks to your pregnancy and the baby.

References

Baschat AA, Galan HL. Fetal growth restriction. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 30.

Brandsma E, Christ LA, Duncan AF. The high-risk infant. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 119.

Mari G, Resnik R. Fetal growth restriction. In: Lockwood CJ, Copel JA, Dugoff L, eds. Creasy and Resnik's Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 44.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 10/15/2024

Reviewed by: John D. Jacobson, MD, Professor Emeritus, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.