Methemoglobinemia

Hemoglobin M disease; Erythrocyte reductase deficiency; Generalized reductase deficiency; MetHb

Methemoglobinemia (MetHb) is a blood disorder in which an abnormal amount of methemoglobin is produced. Hemoglobin is the protein in red blood cells (RBCs) that carries and distributes oxygen to the body. Methemoglobin is a form of hemoglobin.

With methemoglobinemia, the hemoglobin can carry oxygen, but is not able to release it effectively to body tissues.

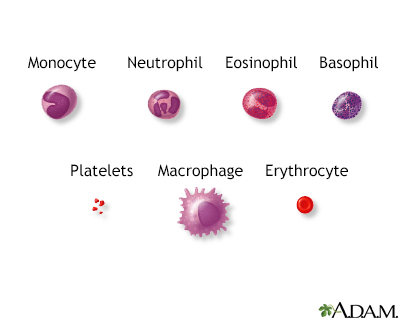

Blood is comprised of red blood cells, platelets, and various white blood cells.

Causes

The MetHb condition can be:

- Passed down through families (inherited or congenital)

- Caused by exposure to certain medicines, chemicals, or foods (acquired)

There are two forms of inherited MetHb. The first form is passed on by both parents due to genetic variants in both. The parents usually do not have the condition themselves. They carry the gene that causes the condition. It occurs when there is a problem with an enzyme called cytochrome b5 reductase.

There are two types of inherited MetHb:

- Type 1 (also called erythrocyte reductase deficiency) occurs when RBCs lack the enzyme.

- Type 2 (also called generalized reductase deficiency) occurs when the enzyme doesn't work in the body.

The second form of inherited MetHb is called hemoglobin M disease. It is caused by defects in the hemoglobin protein itself. Only one parent needs to pass on the variant gene for the child to inherit the disease.

Acquired MetHb is more common than the inherited forms. It occurs in some people after they are exposed to certain chemicals and medicines, including:

- Anesthetics such as benzocaine

- Nitrobenzene

- Certain antibiotics (including dapsone and chloroquine)

- Nitrites (used as additives to prevent meat from spoiling)

Symptoms

Exams and Tests

A baby with this condition will have a bluish skin color (cyanosis) at birth or shortly afterward. Your health care provider will perform blood tests to diagnose the condition. Tests may include:

- Checking the oxygen level in the blood (pulse oximetry)

- Blood test to check levels of gases in the blood (arterial blood gas analysis)

Treatment

People with hemoglobin M disease don't have symptoms. So, they may not need treatment.

A medicine called methylene blue is used to treat severe MetHb. Methylene blue may be unsafe in people who have or may be at risk for a blood disease called G6PD deficiency. They should not take this medicine. If you or your child has G6PD deficiency, always tell your provider before getting treatment.

Ascorbic acid may also be used to reduce the level of methemoglobin.

Alternative treatments include hyperbaric oxygen therapy, red blood cell transfusion and exchange transfusions.

In most cases of mild acquired MetHb, no treatment is needed. But you should avoid the medicine or chemical that caused the problem. Severe cases may need a blood transfusion.

Outlook (Prognosis)

People with type 1 MetHb and hemoglobin M disease often do well. Type 2 MetHb is more serious. It often causes death within the first few years of life.

People with acquired MetHb often do very well once the medicine, food, or chemical that caused the problem is identified and avoided.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you:

- Have a family history of MetHb

- Develop symptoms of this disorder

Call 911 or the local emergency number right away if you have severe shortness of breath.

Prevention

Genetic counseling is suggested for couples with a family history of MetHb and are considering having children.

Babies 6 months or younger are more likely to develop methemoglobinemia. Therefore, homemade baby food purees made from vegetables containing high levels of natural nitrates, such as carrots, beetroots, or spinach should be avoided.

References

Benz Jr EJ, Ebert BL. Hemoglobin variants associated with hemolytic anemia, altered oxygen affinity, and methemoglobinemias. In: Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Silberstein LE, eds. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 44.

Means Jr RT. Approach to the anemias. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 144.

Owusu-Ansah A, Letterio J, Ahuja SP. Red blood cell disorders in the fetus and neonate. In: Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, eds. Fanaroff and Martin's Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 81.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 6/17/2024

Reviewed by: Todd Gersten, MD, Hematology/Oncology, Florida Cancer Specialists & Research Institute, Wellington, FL. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.