Toxic shock syndrome

Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome; Toxic shock-like syndrome; TSLS

Toxic shock syndrome is a serious and potentially life-threatening disease that involves fever, shock, and problems with several body organs.

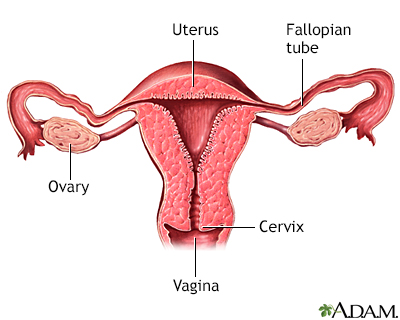

The uterus is a muscular organ with thick walls, two upper openings to the fallopian tubes and an inferior opening to the vagina.

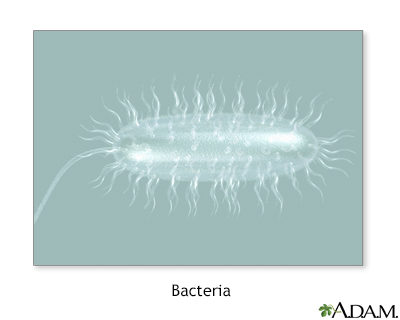

Bacterial infections can lead to the formation of pus, or to the spread of the bacteria in the blood.

An intensive care unit (ICU) is a section of a hospital or health care facility that provides care for patients with life-threatening health problems. These patients need constant monitoring and treatment, which may include support for vital functions. Common types of equipment used in the ICU include cardiac monitoring, mechanical ventilation, feeding tubes, intravenous lines, drains, and catheters. The ICU may also be called an intensive therapy unit or critical care unit.

Causes

Toxic shock syndrome is caused by a toxin produced by some types of staphylococcus bacteria. A similar problem, called toxic shock-like syndrome (TSLS), can be caused by a toxin from streptococcal bacteria. Very few staph or strep infections cause toxic shock syndrome.

The earliest cases of toxic shock syndrome involved women who used tampons during their menstrual periods. However, today less than one half of cases are linked to tampon use. Toxic shock syndrome can also occur with skin infections, burns, and after surgery. The condition can also affect children, postmenopausal women, and men.

Risk factors include:

- Recent childbirth

- Infection with Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus), commonly called a staph infection

- Foreign bodies or packings (such as those used to stop nosebleeds) inside the body

- Recent surgery

- Tampon use (with higher risk if you leave one in for a long time)

- Wound infection after surgery

Symptoms

Symptoms include:

- Confusion

- Diarrhea

- General ill feeling

- Headaches

- High fever, sometimes accompanied by chills

- Low blood pressure

- Muscle aches

- Nausea and vomiting

- Organ failure (most often kidneys and liver)

- Redness of eyes, mouth, throat

- Seizures

- Widespread red rash that looks like a sunburn -- skin peeling occurs 1 or 2 weeks after the rash, particularly on the palms of the hand or bottom of the feet

Exams and Tests

No single test can diagnose toxic shock syndrome.

The health care provider will look for the following factors:

- Fever

- Low blood pressure

- Rash that peels after 1 to 2 weeks

- Problems with the function of at least 3 organs

In some cases, blood cultures may be positive for growth of S aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.

Treatment

Treatment includes:

- Removal of materials, such as tampons, vaginal sponges, or nasal packing

- Drainage of infection sites (such as a surgical wound)

The goal of treatment is to maintain important body functions. This may include:

- Antibiotics for any infection (may be given through an IV)

- Dialysis (if severe kidney problems are present)

- Fluids through a vein (IV)

- Medicines to control blood pressure

- Intravenous gamma globulin in severe cases

- Staying in the hospital intensive care unit (ICU) for monitoring

Outlook (Prognosis)

Toxic shock syndrome may be deadly in up to 50% of cases. The condition may return in those who survive.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Organ damage including kidney, heart, and liver failure

- Shock

- Death

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Toxic shock syndrome is a medical emergency. Seek medical help right away if you develop a rash, fever, and feel ill, particularly during menstruation and tampon use or if you have had recent surgery.

Prevention

You can lower your risk for menstrual toxic shock syndrome by:

- Avoiding highly absorbent tampons

- Changing tampons frequently (at least every 8 hours)

- Only using tampons once in awhile during menstruation

References

Eckert LO, Lentz GM. Genital tract infections: vulva, vagina, cervix, toxic shock syndrome, endometritis, and salpingitis. In: Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA, Lobo RA, eds. Comprehensive Gynecology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 23.

Kroshinsky D. Macular, papular, purpuric, vesiculobullous, and pustular diseases. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 406.

Que Y-A, Moreillon P. Staphylococcus aureus (including staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome). In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 194.

Rapose A. Toxic shock syndrome. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, Heidelbaugh JJ, Lee EM, eds. Conn's Current Therapy 2024. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier 2024:718-719.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 5/23/2024

Reviewed by: Jatin M. Vyas, MD, PhD, Professor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Associate in Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.