Aging changes in the male reproductive system

Andropause; Male reproductive changes

Aging changes in the male reproductive system may include changes in testicular tissue, sperm production, and erectile function. These changes usually occur gradually.

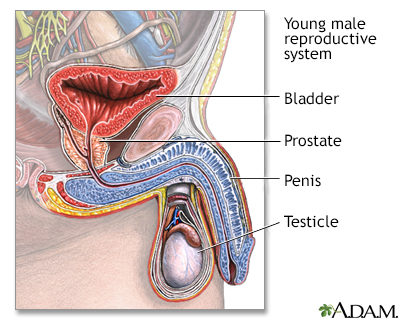

The main function of the male reproductive system is the production of viable sperm in sufficient quantities to increase the likelihood of fertilization of the female egg.

The aged male reproductive system may not be as effective in producing viable sperm.

Information

Unlike women, men do not experience a major, rapid (over several months) change in fertility as they age (like menopause). Instead, changes occur gradually during a process that some people call andropause.

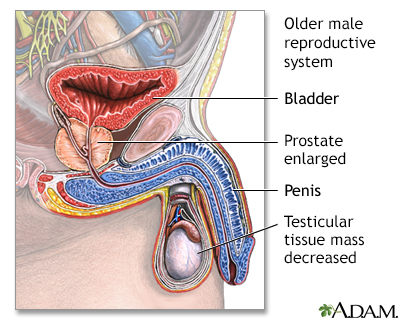

Aging changes in the male reproductive system occur primarily in the testes. Testicular tissue mass decreases. The level of the male sex hormone, testosterone decreases gradually. There may be problems getting an erection. This is a general slowing, instead of a complete lack of function.

FERTILITY

The tubes that carry sperm may become less elastic (a process called sclerosis). The testes continue to produce sperm, but the rate of sperm cell production slows. The epididymis, seminal vesicles, and prostate gland lose some of their surface cells. But they continue to produce the fluid that helps carry sperm.

URINARY FUNCTION

The prostate gland enlarges with age as some of the prostate tissue is replaced with a scar like tissue. This condition, called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), affects about 50% of men. BPH may cause problems with slowed urination and ejaculation.

In both men and women, reproductive system changes are closely related to changes in the urinary system.

EFFECT OF CHANGES

Fertility varies from man to man. Age does not predict male fertility. Prostate function does not affect fertility. A man can father children, even if his prostate gland has been removed. Some fairly old men can (and do) father children.

The volume of fluid ejaculated usually remains the same, but there are fewer living sperm in the fluid.

Some men may have a lower sex drive (libido). Sexual responses may become slower and less intense. This may be related to a decreased testosterone level. It may also result from psychological or social changes due to aging (such as the lack of a willing partner), illness, long-term (chronic) conditions, or medicines.

Aging by itself does not prevent a man from being able to enjoy sexual relationships.

COMMON PROBLEMS

Erectile dysfunction (ED) may be a concern for aging men. It is normal for erections to occur less often than when a man was younger. Aging men are often less able to have repeated ejaculations.

ED is most often the result of a medical problem, rather than simple aging. Ninety percent of ED is believed to be caused by a medical problem instead of a psychological problem.

Medicines (such as those used to treat hypertension and certain other conditions) can prevent a man from getting or keeping enough of an erection for intercourse. Disorders, such as diabetes, can also cause ED.

ED that is caused by medicines or illness is often successfully treated. Talk to your primary health care provider or a urologist if you are concerned about this condition.

BPH may eventually interfere with urination. The enlarged prostate partially blocks the tube that drains the bladder (urethra). Changes in the prostate gland make older men more likely to have urinary tract infections.

Urine may back up into the kidneys (vesicoureteral reflux) if the bladder is not fully drained. If this is not treated, it can eventually lead to kidney failure.

Prostate gland infections or inflammation (prostatitis) may also occur.

Prostate cancer becomes more likely as men age. It is one of the most common causes of cancer death in men. Bladder cancer also becomes more common with age. Testicular cancers are possible, but these occur more often in younger men.

PREVENTION

Many physical age-related changes, such as prostate enlargement or testicular atrophy, are not preventable. Getting treated for health disorders such as high blood pressure and diabetes may prevent problems with urinary and sexual function.

Changes in sexual response are most often related to factors other than simple aging. Older men are more likely to have good sex if they continue to be sexually active during middle age.

RELATED TOPICS

References

Brinton RD. Neuroendocrinology of aging. In: Fillit HM, Rockwood K, Young J, eds. Brocklehurst's Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 13.

Standring S. Male reproductive system. In: Standring S, ed. Gray's Anatomy. 42nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2021:chap 74.

van den Beld AW, Lamberts SWJ. Endocrinology and aging. In: Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB, Koenig RJ, Rosen CJ, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 28.

Walston JD. Common clinical sequelae of aging. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 24.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 7/15/2024

Reviewed by: Frank D. Brodkey, MD, FCCM, Associate Professor, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.