Genetics

Homozygous; Inheritance; Heterozygous; Inheritance patterns; Heredity and disease; Heritable; Genetic markers

Genetics is the study of heredity, the process of a parent passing certain genes to their children. A person's appearance -- height, hair color, skin color, and eye color -- is influenced by genes. Other characteristics influenced by heredity are:

- Likelihood of getting certain diseases

- Mental abilities

- Natural talents

An abnormal trait (variant) that is passed down through families (inherited) may:

- Have no effect on your health or well-being. For example, the trait might just cause a white patch of hair or an earlobe that is longer than normal.

- Have only a minor effect, such as color blindness.

- Have a major effect on your quality or length of life.

For most genetic conditions, genetic counseling is advised for couples who want to become pregnant.

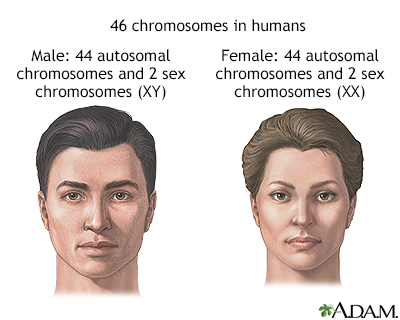

Genetics is the study of heredity and how traits are passed along from parents to offspring. Genes are contained within the chromosomes found in the egg and sperm. Each parent contributes one half of each pair or 23 chromosomes to their child, 22 autosomal and 1 sex chromosome.

Information

Human beings have cells with 46 chromosomes. These consist of 2 chromosomes that determine what sex they are (X and Y chromosomes), and 22 pairs of nonsex (autosomal) chromosomes. Males are "46,XY" and females are "46,XX." The chromosomes are made up of strands of genetic information called DNA. Each chromosome contains sections of DNA called genes. The genes carry the information needed by your body to make certain proteins.

Each pair of chromosomes contains one chromosome from the mother and one from the father. Each chromosome in a pair carries basically the same information; that is, each chromosome pair has the same genes. Sometimes there are slight variations of these genes. These variations occur in less than 1% of the DNA sequence. The genes that have these variations are called alleles.

Some of these variations can result in a gene that is not working properly. A variant gene may lead to an abnormal protein or an abnormal amount of a normal protein. In a pair of autosomal chromosomes, there are two copies of each gene, one from each parent. If one of these genes is abnormal, the other one may make enough protein so that no disease develops. When this happens, the variant gene is called recessive. Recessive genes are said to be inherited in either an autosomal recessive or X-linked pattern. If two copies of the variant gene are present, disease may develop.

However, if only one variant gene is needed to produce a disease, it leads to a dominant hereditary condition. In the case of a dominant condition, if one variant gene is inherited from the mother or father, the child will likely show the disease.

A person with one variant gene is called heterozygous for that gene. If a child receives a variant recessive disease gene from both parents, the child will show the disease and will be homozygous (or compound heterozygous) for that gene.

GENETIC DISORDERS

Almost all diseases have a genetic component. However, the importance of that component varies. Disorders in which genes play an important role (genetic diseases) can be classified as:

- Single-gene variants

- Chromosomal conditions

- Multifactorial

A single-gene condition (also called Mendelian disorder) is caused by a variant in one particular gene. Many conditions caused by single gene variants are rare. But since there are many thousands of known single gene conditions, their combined impact is significant.

Single-gene conditions are characterized by how they are passed down in families. There are 6 basic patterns of single gene inheritance:

- Autosomal dominant

- Autosomal recessive

- X-linked dominant

- X-linked recessive

- Y-linked inheritance

- Maternal (mitochondrial) inheritance

The observed effect of a gene (the appearance of a condition) is called the phenotype.

In autosomal dominant inheritance, the variations usually appear in every generation. Each time an affected parent, either male or female, has a child, that child has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease.

People with one copy of a recessive disease gene are called carriers. Carriers usually don't have symptoms of the disease. But, the gene can often be found by sensitive laboratory tests.

In autosomal recessive inheritance, the parents of an affected individual may not show the disease (they are carriers). On average, the chance that carrier parents could have children who develop the disease is 25% with each pregnancy. Male and female children are equally likely to be affected. For a child to have symptoms of an autosomal recessive disorder, the child must receive the variant gene from both parents. Because most recessive disorders are rare, a child is at increased risk of a recessive disease if the parents are related. Related individuals are more likely to have inherited the same rare gene from a common ancestor.

In X-linked recessive inheritance, the chance of being affected with the disease is much higher in males than females. Since the variant gene is carried on the X (female) chromosome, males do not transmit it to their sons (who will receive the Y chromosome from their fathers). However, they do transmit it to their daughters. In females, the presence of one normal X chromosome masks the effects of the X chromosome with the variant gene. So, almost all of the daughters of an affected man appear normal, but they are all carriers of the variant gene. Each time these daughters bear a son, there is a 50% chance the son will receive the variant gene.

In X-linked dominant inheritance, the variant gene appears in females, causing the associated condition, even if there is also a normal X chromosome present. Since males pass the Y chromosome to their sons, affected males will not have affected sons. All of their daughters will be affected, however. Sons or daughters of affected females will have a 50% chance of getting the disease. Many of these diseases are fatal in males.

EXAMPLES OF SINGLE GENE DISORDERS

Autosomal recessive:

- ADA deficiency (sometimes called the "boy in a bubble" disease)

- Alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency

- Cystic fibrosis (CF)

- Phenylketonuria (PKU)

- Sickle cell anemia

X-linked recessive:

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- Hemophilia A

Autosomal dominant:

X-linked dominant:

Only a few, rare, disorders are X-linked dominant. One of these is hypophosphatemic rickets, also called vitamin D -resistant rickets.

CHROMOSOMAL DISORDERS

In chromosomal disorders, the variant is due to either an excess or lack of the genes contained in a whole chromosome or chromosome segment.

Chromosomal disorders include:

- 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome

- Down syndrome

- Klinefelter syndrome

- Turner syndrome

MULTIFACTORIAL DISORDERS

Many of the most common diseases are caused by interactions of several genes and factors in the environment (for example, illnesses in the mother and medicines). These include:

MITOCHONDRIAL DNA-LINKED DISORDERS

Mitochondria are small structures found in most of the body's cells. They are responsible for energy production inside cells. Mitochondria contain their own private DNA.

In recent years, many disorders have been shown to result from changes (variations) in mitochondrial DNA. Because mitochondria come only from the female egg, most mitochondrial DNA-related disorders are passed down from the mother.

Mitochondrial DNA-related disorders can appear at any age. They have a wide variety of symptoms and signs. These disorders may cause:

- Blindness

- Developmental delay

- Gastrointestinal problems

- Hearing loss

- Heart rhythm problems

- Metabolic disturbances

- Short stature

Some other disorders are also known as mitochondrial disorders, but they do not involve variations in the mitochondrial DNA. These disorders are most often single gene variants. They follow the same pattern of inheritance as other single gene disorders. Most are autosomal recessive.

References

Feero WG, Zazove P, Chen F. Clinical genomics. In: Rakel RE, Rakel DP, eds. Textbook of Family Medicine. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 43.

Korf BR, Limdi NA. Principles of genetics. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 31.

Scott DA, Lee B. Genetics in pediatric medicine. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 95.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 3/31/2024

Reviewed by: Anna C. Edens Hurst, MD, MS, Associate Professor in Medical Genetics, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.