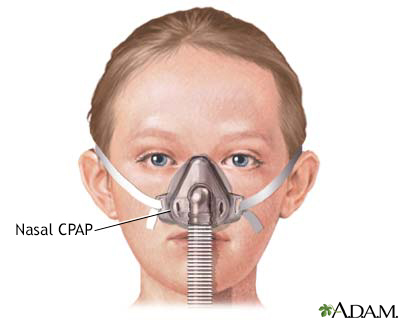

Nasal CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure; CPAP; Bilevel positive airway pressure; BiPAP; Autotitrating positive airway pressure; APAP; nCPAP; Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation; NIPPV; Non-invasive ventilation; NIV; OSA - CPAP; Obstructive sleep apnea - CPAP

Positive airway pressure (PAP) treatment uses a machine to pump air under pressure into the airway of the lungs. This helps keep the windpipe open during sleep. The forced air delivered by CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) prevents episodes of airway collapse that block the breathing in people with obstructive sleep apnea and other breathing problems.

CPAP is an airway treatment that applies a constant pressure of forced air to keep the airway open.

Information

WHO SHOULD USE PAP

PAP can successfully treat most people with obstructive sleep apnea. It is safe and works well for people of all ages, including children. If you only have mild sleep apnea and do not feel very sleepy during the day, you may not need it.

After using PAP regularly, you may notice:

- Better concentration and memory

- Feeling more alert and less sleepy during the day

- Improved sleep for your bed partner

- Being more productive at work

- Less anxiety and depression and a better mood

- Normal sleep patterns

- Lower blood pressure (in people with high blood pressure)

Your health care provider will prescribe the type of PAP machine that targets your problem:

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) provides a gentle and steady pressure of air in your airway to keep it open.

- Autotitrating (adjustable) positive airway pressure (APAP) changes pressure throughout the night, based on your breathing patterns.

- Bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP or BIPAP) has a higher pressure when you breathe in and lower pressure when you breathe out.

BiPAP is useful for children and adults who have:

- Airways that collapse while sleeping, making it hard to breathe freely

- Decreased air exchange in the lung

- Muscle weakness that makes it difficult to breathe, due to conditions such as muscular dystrophy

PAP or BiPAP may also be used by people who have:

HOW PAP WORKS

When using a PAP setup:

- You wear a mask over your nose or nose and mouth while you sleep.

- The mask is connected by a hose to a small machine that sits at the side of your bed.

- The machine pumps air under pressure through the hose and mask and into your airway while you sleep. This helps keep your airway open.

You may start to use PAP while you are in a sleep center for the night. Some newer machines (self-adjusting or auto-PAP), may be set up for you and then just given to you to sleep with at home, without the need for a test to adjust the pressures.

- Your provider will help choose the mask that fits you best.

- They will adjust the settings on the machine while you are asleep.

- The settings will be adjusted based on the severity of your sleep apnea.

If your symptoms don't improve after you're on PAP treatment, the settings on the machine may need to be changed. Your provider may teach you how to adjust the settings at home. Or, you may need to go to the sleep center to have it adjusted.

GETTING USED TO THE MACHINE

It can take time to get used to using the PAP setup. The first few nights are often the hardest and you may not sleep well.

If you are having problems, you may be tempted not to use the machine for the whole night. But you will get used to it more quickly if you use the machine for the entire night.

When using the setup for the first time, you may have:

- A feeling of being closed in (claustrophobia)

- Chest muscle discomfort, which often goes away after awhile

- Eye irritation

- Redness and sores over the bridge of your nose

- Runny or stuffed-up nose

- Sore or dry mouth

- Nosebleeds

- Upper respiratory infections

Many of these problems can be helped or prevented.

- Ask your provider about using a mask that is lightweight and cushioned. Some masks are used only around or inside the nostrils.

- Make sure the mask fits correctly so that it does not leak air. It should not be too tight or too loose.

- Try nasal salt water sprays for a stuffy nose.

- Use a humidifier to help with dry skin or nasal passages.

- Keep your equipment clean.

- Place your machine underneath your bed to limit noise.

- Most machines are quiet, but if you notice sounds that make it hard to sleep, tell your provider.

Your provider can lower the pressure on the machine and then increase it again at a slow pace. Some new machines can automatically adjust to the right pressure.

References

Freedman N, Johnson K. Positive airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Goldstein CA, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 132.

Kimoff RJ, Kaminska M, Pamidi S. Obstructive sleep apnea. In: Broaddus VC, King TE, Ernst JD, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 120.

Patil SP, Ayappa IA, Caples SM, Kimoff RJ, Patel SR, Harrod CG. Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(2):335-343. PMID: 30736887

Shangold L, Jacobowitz O. CPAP, APAP, and BiPAP. In: Friedman M, Jacobowitz O, eds. Sleep Apnea and Snoring. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 8.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 4/20/2023

Reviewed by: Allen J. Blaivas, DO, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, VA New Jersey Health Care System, Clinical Assistant Professor, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, East Orange, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Internal review and update on 02/10/2024 by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.