Intercostal retractions

Retractions of the chest muscles

Intercostal retractions occur when the muscles between the ribs pull inward. The movement is most often a sign that the person has a breathing problem.

Intercostal retractions are a medical emergency.

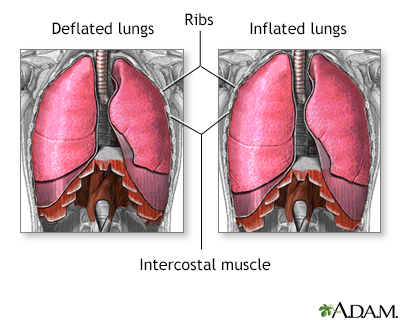

Breathing consists of two phases. The first phase is the inspiration phase. Inspiration allows air to flow into the lungs. The second phase is expiration. Expiration involves gases leaving the lungs. During inspiration, the diaphragm and intercostal muscles contract allowing air to enter the lungs. During expiration, the inspiration muscles relax forcing gases to flow out of the lungs.

Considerations

The wall of your chest is flexible. This helps you breathe normally. Stiff tissue called cartilage attaches your ribs to the breast bone (sternum).

The intercostal muscles are the muscles between the ribs. During breathing, these muscles normally tighten and pull the rib cage up. Your chest expands and the lungs fill with air.

Intercostal retractions are due to reduced air pressure inside your chest. This can happen if the upper airway (trachea) or small airways of the lungs (bronchioles) become partially blocked. As a result, the intercostal muscles are sucked inward, between the ribs, when you breathe. This is a sign of a partially or completely blocked airway. Any health problem that causes a blockage in the airway will cause intercostal retractions.

Causes

Intercostal retractions may be caused by:

- A severe, whole-body allergic reaction called anaphylaxis

- Asthma

- Swelling and mucus buildup in the smallest air passages in the lungs (bronchiolitis)

- Problem breathing and a barking cough (croup)

- Inflammation of the tissue (epiglottis) that covers the windpipe

- Foreign body in the windpipe

- Pneumonia

- A lung problem in newborns called respiratory distress syndrome

- Collection of pus in the tissues in the back of the throat (retropharyngeal abscess)

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Seek medical help right away if intercostal retractions occur. This can be a sign of a blocked airway, which can quickly become life threatening.

Also seek medical care if the skin, lips, or nailbeds turn blue (cyanosis), or if the person becomes confused, drowsy, or is hard to wake up.

What to Expect at Your Office Visit

In an emergency, your health care team will first take steps to help you breathe. You may receive oxygen, medicines to reduce swelling, and other treatments.

When you can breathe better, your health care provider will examine you and ask about your medical history and symptoms, such as:

- When did the problem start?

- Is it getting better, worse, or staying the same?

- Does it occur all the time?

- Did you notice anything significant that might have caused an airway obstruction?

- What other symptoms are there, such as blue skin color, wheezing, high-pitched sound when breathing (stridor), coughing or sore throat?

- Has anything been breathed into the airway?

Tests that may be done include:

- Arterial blood gases

- Chest x-ray

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Pulse oximetry to measure blood oxygen level

References

Brown CA, Walls RM. Airway. In: Walls RM, ed. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 1.

Rodrigues KK, Roosevelt GE. Acute inflammatory upper airway obstruction (croup, epiglottitis, laryngitis, and bacterial tracheitis). In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 433.

Stephany A. Respiratory distress. In: Kliegman RM, Toth H, Bordini BJ, Basel D, eds. Nelson Pediatric Symptom-Based Diagnosis. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 4.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 4/1/2024

Reviewed by: Charles I. Schwartz, MD, FAAP, Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, General Pediatrician at PennCare for Kids, Phoenixville, PA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.