Audiometry

Audiometry; Hearing test; Audiography (audiogram)

An audiometry exam tests your ability to hear sounds. Sounds vary, based on their loudness (intensity) and the speed of sound wave vibrations (tone).

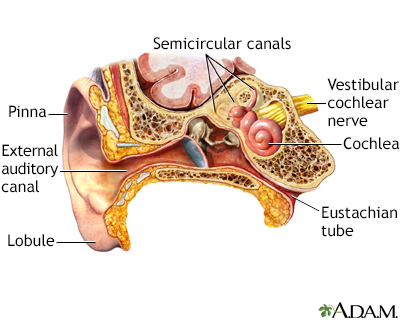

Hearing occurs when sound waves stimulate the nerves of the inner ear. The sound then travels along nerve pathways to the brain.

Sound waves can travel to the inner ear through the ear canal, eardrum, and bones of the middle ear (air conduction). They can also pass through the bones around and behind the ear (bone conduction).

The INTENSITY of sound is measured in decibels (dB):

- A whisper is about 20 dB.

- Loud music (some concerts) is around 80 to 120 dB.

- A jet engine is about 140 to 180 dB.

Sounds greater than 85 dB can cause hearing loss after a few hours. Louder sounds can cause immediate pain, and hearing loss can develop in a very short time.

The TONE of sound is measured in cycles per second (cps) or Hertz (Hz):

- Low bass tones range around 50 to 60 Hz.

- Shrill, high-pitched tones range around 10,000 Hz or higher.

The normal range of human hearing is about 20 to 20,000 Hz. Some animals can hear up to 50,000 Hz. Human speech is usually 500 to 3,000 Hz.

The ear consists of external, middle, and inner structures. The eardrum and the three tiny bones conduct sound from the eardrum to the cochlea.

How the Test is Performed

Your health care provider may test your hearing with simple tests that can be done in the office. These may include completing a questionnaire and listening to whispered voices, tuning forks, or tones from an ear examination scope.

A specialized tuning fork test can help determine the type of hearing loss. The tuning fork is tapped and held in the air on each side of the head to test the ability to hear by air conduction. It is tapped and placed against the bone behind each ear (mastoid bone) to test bone conduction.

A formal hearing testing can give a more exact measure of hearing. Several tests may be done:

- Pure tone testing (audiogram) -- For this test, you wear earphones attached to the audiometer. Pure tones of a specific frequency and volume are delivered to one ear at a time. You are asked to signal when you hear a sound. The minimum volume required to hear each tone is graphed. A device called a bone oscillator is placed against the mastoid bone to test bone conduction.

- Speech audiometry -- This tests your ability to detect and repeat spoken words at different volumes heard through a head set.

- Immittance audiometry -- This test measures the function of the ear drum and the flow of sound through the middle ear. A probe is inserted into the ear and air is pumped through it to change the pressure within the ear as tones are produced. A microphone monitors how well sound is conducted within the ear under different pressures.

- Tympanometry -- A measure of the vibration of the ear drum and middle ear pressure.

How to Prepare for the Test

No special steps are needed.

How the Test will Feel

There is no discomfort. The length of time varies. An initial screening may take about 5 to 10 minutes. Detailed audiometry may take about 1 hour.

Why the Test is Performed

This test can detect hearing loss at an early stage. It may also be used when you have hearing problems from any cause.

Normal Results

Normal results include:

- The ability to hear a whisper, normal speech, and a ticking watch is normal.

- The ability to hear a tuning fork through air and bone is normal.

- In detailed audiometry, hearing is normal if you can hear tones from 250 to 8,000 Hz at 25 dB or lower.

What Abnormal Results Mean

There are many kinds and degrees of hearing loss. In some types, you only lose the ability to hear high or low tones, or you lose only air or bone conduction. The inability to hear pure tones below 25 dB indicates some hearing loss.

The amount and type of hearing loss may give clues to the cause, and chances of recovering your hearing.

The following conditions may affect test results:

- Acoustic neuroma

- Acoustic trauma from a very loud or intense blast sound

- Age-related hearing loss

- Alport syndrome

- Chronic ear infections

- Labyrinthitis

- Ménière disease

- Ongoing exposure to loud noise, such as at work or from music

- Abnormal bone growth in the middle ear, called otosclerosis

- Ruptured or perforated eardrum

Risks

There is no risk.

Considerations

Other tests may be used to determine how well the inner ear and brain pathways are working. One of these is otoacoustic emission testing (OAE) that detects sounds given off by the inner ear when responding to sound. This test is often done as part of a newborn screening. A head MRI may be done to help diagnose hearing loss due to an acoustic neuroma.

References

Amundsen GA. Audiometry. In: Fowler GC, ed. Pfenninger and Fowler's Procedures for Primary Care. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 59.

Kileny PR, Zwolan TA, Slager HK. Diagnostic audiology and electrophysiologic assessment of hearing. In: Flint PW, Francis HW, Haughey BH, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 134.

Lew HL, Tanaka C, Pogoda TK, Hall JW. Auditory, vestibular, and visual impairments. In: Cifu DX, ed. Braddom's Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 50.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 5/2/2024

Reviewed by: Josef Shargorodsky, MD, MPH, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.