Theater of War

Date Published: November 18, 2020

How can Ancient Greek tragedies help communities—from front-line healthcare workers to military veterans—build resilience in the face of stress and trauma? Since 2009, Theater of War Productions has used this “ancient technology” to break cultures of silence and spark cathartic conversations. In this interview, artistic director Bryan Doerries explains how each performance, which consists of a reading by A-list actors followed by a candid audience discussion, can open a door to healing.

Podcast Transcript

Host: 00:00

From the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. This is Road to Resilience, a podcast about facing adversity. I'm Jon Earle.

Actors: 00:11

At which men's feet am I now splayed out like a cold corpse, exhausted by the endless waves of pain? Oh, God. Here comes the misery. Here comes the hateful plague again to ravage my body, to eat me alive. I am asking you to be my doctor, heal this affliction, cure my disease! I wanted to keep the pain to myself, son. But now it cuts straight through me. Do you understand? It cuts straight through me. I am being eaten alive. Death, death, death. Where are you?

Host: 00:50

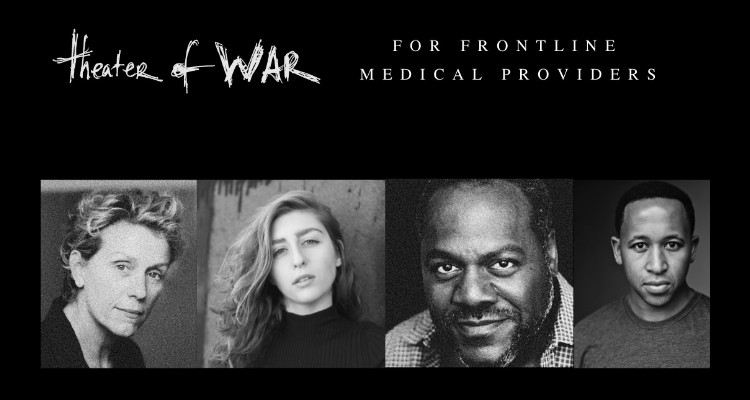

That was actors Frances McDormand and Frankie Faison performing ancient Greek tragedies over Zoom. My guest today is Bryan Doerries. He's a writer, translator, director and the artistic director of Theater of War Productions. For over a decade, Theater of War has been performing Greek tragedies for communities under extreme stress. These include Marines, prison guards, front-line health workers, and many, many others. The plays are performed by A-list actors and are riveting in their own right. But the real magic happens afterwards, during the audience discussion. The plays spark honest conversations about pain, grief, and other struggles. I don't think it's too much to call them cathartic. In our conversation, Bryan talks about how these plays can help us wrestle with pain together, as communities, rather than in isolation, which is what happens way too often. Theater of War is performing a special program for front-line medical providers on Thursday, November 19th at 7PM Eastern. That's the day after this podcast comes out. The event is hosted by Mount Sinai, but it's free and open to the public. So please reserve tickets by following the link in the show notes. Okay. Here's Bryan Doerries. I hope you enjoy the conversation. Bryan Doerries, welcome to Road to Resilience.

Bryan Doerries: 02:07

Thanks so much for the invitation.

Host: 02:10

I'd like to begin with a performance that I saw a couple of weeks ago for a group of front-line workers in Queens. And I have to be completely honest, I was a little skeptical when I first heard of the idea—performing ancient Greek plays for a group of very busy people in the middle of their workday. I was honestly expecting a polite-applause sort of response. Like "thank you all for doing this." And so I was completely surprised by the passionate, full-throated, open, honest conversation that ensued afterwards. And I then watched another performance with UK service members as the audience, and I saw the same thing. So my first question for you is why is it that these ancient Greek plays, written over 2,000 years ago, produce that kind of response?

Bryan Doerries: 02:57

Well, part of the answer to your question actually has little to do with the plays and everything to do with the depravity of what characterizes communication in institutional settings. So for a lot of the big issues that we try to address with our work, the dominant mode of discourse often is PowerPoint presentations or didactic lectures or panel discussions where experts speak from authority. And what performing Greek tragedies do in institutional settings, where people, for whatever series of reasons, practice a kind of clinical detachment from their emotions and from the moral and spiritual consequences of their daily decisions, is they kind of disrupt all of that and they create a new type of communication. And I think that's what the plays were designed to do in the ancient world. And that's why they work. They're almost like external hard drives. You can dust them off and plug them into the right audience and the plays know what to do. But I think even more tellingly the audiences know what to do just as you described in your experience of watching them.

And I was equally skeptical and sort of afraid the first time we did a performance of a Greek play for 400 Marines in the Hyatt ballroom in San Diego back in 2008. At that time it was seen as a career-ending gesture in the military to say, "I'm struggling with an invisible wound." Just as it is still seen as a career-ending gesture in many medical centers and hospitals to acknowledge one's moral suffering. And the difference between someone seeking help or engaging in a sort of path to healing and not could be whether the actors reach them in the performance. So if someone had told me 15 years ago that performing Greek plays for institutional audiences that practice clinical detachment could be of life and death significance for the audiences listening to them, I would say that sounds ridiculous and hyperbolic and crazy. But I can't tell you the number of people who've come up to us, either in the discussions that result from the performances of these ancient texts or simply afterwards, or even sometimes months afterwards and said, "That was the first time I ever spoke to my spouse about what I'd experienced," or "That's the first time I heard my father speak about his experience," or "I saw myself reflected in the character and I checked myself into a 28-day alcohol treatment program the next morning," or "I was thinking about taking my own life and I sought help," or even, we've had people come forward and say, "I was thinking about committing an act of violence, and this gave me pause. And I talked to a mental health professional." This sounds grandiose, but now 1,700 performances in, it's become commonplace. And that's because I think these larger moral and spiritual questions that we're after deserve a much more complex and dynamic medium than PowerPoint or panel discussions or CME grand rounds.

Host: 06:13

You're clearly familiar with healthcare.

Bryan Doerries: 06:16

Is there something that reaches and penetrates past people's defenses and touches them in a way that they could never have imagined? And that's why in some ways it's good that you come as a skeptic. I hope people are skeptical. And then I hope people are reminded by virtue of what happens in our discussions that follow the performances of what's actually possible when we imbue these exchanges that we're all yearning to have but don't know how to with spirit and humanity. And that's what it's about.

Host: 06:47

I gotta say I've never seen a better conversation—to say it's about literature or about Greek plays is a disservice to what it's about. It was as if the people who were speaking knew these plays their entire life. They knew them inside and out, they were responding specifically, line-by-line to things. Viscerally. Perceptively. I'd never seen anything like it.

Bryan Doerries: 07:07

Well, it turns out that higher education is, for lack of a better word, an extension of the various structures of oppression that we try to address with our work. And the primary myth of training and of higher education in the humanities but also in medicine is that only those who've had the privilege of that training can understand these complex ethical situations and questions. What if, in fact, only those who've lived the extremities of life who've faced life and death, who've loved, who've lost, who know the meaning of sacrifice, who've been betrayed—only they actually have access to what these stories are speaking to. And that no matter of training, no amount of education or privilege can actually give you that access. And so the big revelation for us early—so I'm just backing up to your original question—we started in hospitals before we went to the military. Our first performance was at Weill Cornell Medical.

Host: 08:11

Oh, I didn't know that.

Bryan Doerries: 08:11

And that was because, in fact, I had been a caregiver for my twenties, a large portion of my twenties, for my girlfriend that died of cystic fibrosis named Laura Rothenberg, and then my father. Laura had a double lung transplant and died 20 months later. And I was her caregiver for a portion of that time at the end. And my father, just a few years later, had a kidney transplant and I found myself thrust into the outer rim of what constituted medicine, like the frontiers of medicine where there was no data to support what's going to happen next. And as caregivers, you just find yourself in that unmoored space with doctors and clinicians and nurses, trying to figure it out in real time. And, it was a real education for me to move past my own ambivalence in the face of their suffering, my girlfriend and my father, or reckon with the limits of my own compassion, which is something I think that people don't discuss. To grapple with how alone one feels when facing complex ethical decisions and why we have a culture that relegates those of us who are facing those decisions to the closet when in fact they should be happening in the amphitheater. And so I went back to these Greek plays, after I lost my girlfriend, that I had studied in college and translated and loved. And all of a sudden it was if they were written about me or for me, or with me in mind. And they were speaking to my hidden conflicts. And I got this idea of—if I could perform them in settings where people also had faced these complex questions that something powerful would happen. And that was back in 2006, 2007. So that's the idea. We started there and that led to the military and military led to prison, and prison led to end-of-life care. And now we have 27 projects and they're all addressing these public health and social issues through this basic format that you saw modeled every time.

Host: 10:20

One thing I noticed was that the plays don't pull any punches. And in the performances that I saw, in both of them, there is a character wailing on stage for a long period of time. It's hard to watch. And you write in your book that early on you were warned. People said this would be re-traumatizing in addition to going over people's heads. But I think there's something in the very intensity of the plays that's the key to their success, and I was wondering if you could speak to that.

Bryan Doerries: 10:50

Yes. So in all of the plays we perform from the ancient world there is inevitably a moment for each character where there is an opportunity to push past what is appropriate or consumable in traditional cultural or an institutional settings to something that is actually so uncomfortable to witness that for a moment, all of us are scanning for the exits. In the early days we were careful. We were warned by mental health professionals, "Please be mindful of the unintended consequences of performing such intense scenes for people who've experienced trauma." And so that's why, in the early days, we piloted it in a number of locations. But counterintuitively, what we started to see in audiences that had experienced trauma when they were confronted with these scenes of abject suffering and sort of depravity and wailing, as you described, was the exact opposite of what everyone had warned us we might see, which was—people were smiling. People were laughing. People came up, not laughing derisively, but laughing with recognition. People afterwards would come up to us and report that they were buzzing. And the conversations that started—. The first time we did one of these, we scheduled the discussion afterwards for 45 minutes. It lasted three and a half hours and had to be cut off at midnight. If you bottled the psychic energy in the room after these performances, it could light Manhattan for a week. And I tell the actors, the note I give them is, "Make them wish they'd never come." Before they go on stage. And a lot of them really wrestle with that. They're like, "What do you mean?" And I say, "If there's a sound that comes up out of you, make sure it's a sound you've never heard before. A sound that surprises you when it comes out of you." And then maybe you'll be doing something actually of service for this audience. Because we're not going to perform the play and then check the box that we performed it. We're going to perform part of the play, and then we're going to break it, and we're going to interrogate why we were so uncomfortable watching it. And if you make everybody uncomfortable in the room for a few seconds, no matter what divides us politically, or in terms of our class or race, or in terms of all the things that divide us as a culture, at least we have that discomfort in common. And we can begin a conversation from interrogating what makes us so uncomfortable about watching and feeling complicit in the suffering of people that we might be allegedly serving or loving or caring for in some way. What makes us so uncomfortable? And then in talking about it, we don't have to talk about ourselves. You can talk about the characters. You can step out from behind the characters. You can talk about the archetypes. You can step out and say, "No, actually I am that character." But it's your choice. You have the consent. You have the agency to make that choice.

Host: 13:48

What are some of the traps that you've learned to avoid in the way that you talk about the project and the way you facilitate and the way that you respond and arrange the conversation?

Bryan Doerries: 13:58

Yeah, I think the biggest issue in our society and our culture—and this goes back to, you know, I don't mean to dismiss the concerns of mental health professionals when they worry about re-traumatizing people—but I think sometimes those concerns are not born out of concern for people and their trauma, and much more about controlling the narrative and the structure of discussion and how discourse takes place. And we live in a very repressive society. It's waking up. It's crawling up out of the sludge of the 19th century. It's finally emerging to a place where, by virtue and, I think, by force of the millennial generation that's demanding we talk about power and privilege and consent and dynamics in an entirely different way than any generation before, we're finally talking about it without shame. And we're seeing this impulse to talk. But we have massive, age-old, repressive tendencies in our culture to silence people when they speak about their trauma, to relegate people who've experienced death and dying to the shadows, even within medicine. Palliative care and hospice is relegated to the sidelines as if it isn't medicine. But, in fact, there's probably more medicine between when a person is no longer treatable in the traditional sense of the word and when they die than everything that preceded it. And we're only now just waking up to what that might mean. What would it mean for us if we treated that stage of life before death as an intrinsic part of what it means to be healers and be involved in medicine? I would say the biggest trap—to go back to your question—is in the early days, as a facilitator, I used to try to protect people from hurtful things that might be said. As an example, there are a lot of people on the left who even if they're still paying their taxes and they still at some level believe that it's important not to criminalize our military, our volunteer military class, there's still an impulse within them to condescend to the military. You know, "You all are pawns. You have no idea what these larger forces that work upon you are doing or manipulating you to do." So I used to step into the breach and start to speak on behalf of veterans. And actually it's a more condescending gesture to do that than what the person said that preceded it, which is to say there's nothing that veterans or doctors or patients or people experiencing homelessness or people who've experienced trauma haven't already heard or thought about themselves. So creating a venue and a space where they can respond for themselves. If something hurtful or hateful or uncomfortable gets said in the discussion, it's always inevitably the most productive things that get said, because at least we're now acknowledging what so many people in the room are thinking but they don't have the courage to say.

I often cite the example, when we talk about suicide, of how we were performing for Marines in North Carolina. And during the discussion of Sophocles' Ajax, a Marine stood up and said, "I think that everyone who considers suicide—" and Ajax commits suicide on stage in Sophocles' play—"I think everyone who thinks about suicide is a coward and they deserve to die." Well, in the early days of Theater of War, I would have jumped into the breach and tried to contextualize what that person had said and create a more comfortable environment for everyone to have this conversation. But I have learned that, in fact, there is a fascistic impulse on both sides of the aisle of our politics these days to censor speech and to not treat ourselves as fully capable adults who are able to have these conversations. And so I've learned to step back and always trust in the wisdom of the audience, not just a random audience, but the audience with something at stake. So in that instance, a giant Marine five times larger than I'd ever envisioned stood up, and he took the microphone out of my hand. I had no idea what he was going to say. And he leaned in and he said to the audience, "Everyone here knows I'm the hardest Marine in this room." And no one denied his statement. And then he said, "There's a war going on inside my mind. I think about suicide every single day. And you can't see it." And he tells his story and everyone listens with rapt attention. And then he says, "So I hope you don't think that I'm a coward." So what could be more powerful than a Marine three times my size picking up the microphone and saying what he said. And he turns to me and he says, "If you'll excuse me, Bryan, I have to go to my therapy session." And he leaves the room and everyone gives him a standing applause, maybe everyone, except for a couple of Marines who didn't share in the enthusiasm. But the crowd with skin in the game, with something at stake had something to say, which is that strength is in admitting your vulnerability. It's in acknowledging that psychological struggles that come from trauma and moral suffering are the hardest struggles there are on the planet.

Host: 19:14

Something that struck me during the performances is that you are a very intense listener. You listen to each of the people who are speaking, each of the panelists, each of the members of the audience who speak intensely, and you offer a response that's not just, "Thank you for coming. Thank you for speaking." First of all, you never correct people's pronunciation. You do a number of things that are just like built-in respect that I feel like you've learned over the years to do.

Bryan Doerries: 19:43

Yeah. I mean who cares about pronunciation and who cares—I mean, I had to speak Greek with three different professors, three different ways—

Host: 19:50

But they're these small things that signal—

Bryan Doerries: 19:53

They accrue. There are so many things we do that accrue to telling people to shut up. that accrue to telling people this isn't for you. You have no authority. You have no business speaking here. When we did our performance most recently for another hospital that was hit very hard by COVID, Lincoln Medical Center in the Bronx, we made sure that the panel of people who were responding before we got to the larger audience was really reflective of the front lines. And by the front lines we meant doctors and nurses, but we also meant security guards, greeters. And then during the discussion, if we've done our work and that sense of respect and of listening and reverence is really modeled, not just by me, but by the panelists on screen, then something really magical happens. Someone raises their hand, and that day it was a woman named Modesia. She goes by Mo and she says, essentially, I'm a custodial worker here at the hospital. And I clean the rooms of patients who have COVID after they die,

Host: 20:54

Here's a clip of Mo.

Mo: 20:56

We clean up after someone either passes away or gets discharged. So when we go in the room we feel death. And it's like, I'm empathetic, so I'm ready to cry. And I gotta stop and bring myself back and do my job and make sure I do it to the best of my ability, because by me cleaning this room, I'm actually sanitizing for the next person, the next doctor, the next nurse, to make sure everyone is okay. When you go outside, you get people. "That's not real. That's fake. That's government-made." But you're seeing it first hand so you know it's real.

Bryan Doerries: 21:29

And then goes on to talk about the gun violence that she goes home and experiences in her community when she goes home and worries that she's going to infect her children from the very job that she's stood up to do at this community hospital, this public hospital in the Bronx. The only way to create the conditions where the custodial worker stands up and speaks the truth of their experience and then explicates all the themes in the play in ways that—I would contend in some ways education and privilege are an impediment to understanding—is by listening with true reverence and respect for what people know that we, by virtue of our privilege and our education, can't. And so that's what my approach to listening and facilitating is born out of. The audience knows more than we do. And 99 percent of the time, whether you're in medicine or you're in culture, we spend most of our time pretending like we're the shamans, we're the gods bestowing the gift of our profession on others. What new things are possible when we approach those we serve with reverence for what they know, or our colleagues for what they know that we cannot know and that we need their help to understand.

Host: 22:47

That's what the "ancient technology," as you put it, that's what it does.

Bryan Doerries: 22:52

That's it. And you see on display, you know, the Greeks aren't perfect. In fact, they're hugely flawed. It's like misogyny and slavery and aristocracy and patriarchy and all these things that are on display, but we're not proselytizing those things. We're just creating an environment where people can interrogate those themes and many more in their own communities. So the other thing about your first question, why do they work—it's because we're not doing documentary theater. There are a lot of efforts since COVID hit to represent the medical community back to itself. I won't malign the plays or the television or anything that's been written, just to say that I think the medium is the message. And when you have actors trying to portray a community to itself, all communities are highly nuanced and coded and more complicated than the actor could ever intuitively understand without studying it for many years. You're always presenting this thing that has this tension, and it always inherently is an act of condescension to a certain extent. But if you perform a Greek play or Shakespearian play, or the Book of Job, which we're doing in a few weeks, or something from the Far East, and you do it for an audience that may or may not have any connection with that culture, you're basically saying, "I'm not saying this is you. I'm not accusing you of anything. I'm just asking you to reflect as a community. What do you see of yourself in this ancient and somewhat distant thing?" That's not saying that these plays shouldn't feel direct. They should. There's a reason why when most of us hear about Greek drama we think of people wearing togas and sandals and pouring hot candle wax on their hands and then acting sort of fake rituals that make no sense in the contemporary world. I think these plays demand an enormous amount of imagination.

Host: 24:55

Bryan, speaking of the plays, a few days after this podcast comes out, you're going to be doing the performance, via Zoom with the Mount Sinai group. What are the plays that you're going to be performing and why those plays for this audience?

Bryan Doerries: 25:08

We are doing two scenes from two ancient Greek plays by Sophocles. Sophocles who was a general in the Athenian army. Sophocles who lived to be 90 years old and saw the arc of the fifth century BC, a century in which the Greeks had seen nearly 80 years of war and also a pestilence that killed one third of the Athenian population, we now believe to be typhoid fever. We perform these two scenes from these two plays. The first we perform this play called Philoctetes. And in a nutshell it's a play about a wounded warrior who is abandoned on an island on the way to the Trojan War on account of a chronic illness he develops after being bitten by a snake that seemingly has no cure or no medicine that can really alleviate it. So his screams and his discomfort are the very thing that compel his fellow soldiers and the very people he led there to abandon him for dead on this Island. And nine years later, the Greeks learn from an oracle that in order to win the Trojan War they have to go back and get him and his weapons, invincible weapons, his bow and arrow, and bring them to Troy.

At the core of the play is this question about clinical detachment, but not just the clinical detachment that doctors are indoctrinated into practicing, or clinicians, but also the clinical detachment we all practice every day to get home from work. If we let in all the suffering that's around us all the time, especially in New York City, we would be so overwhelmed that we wouldn't be able to attend to our families. We wouldn't be able to attend to ourselves. So we practice clinical detachment. But what the Greeks knew that we've lost touch with as a culture is there has to be a time. There has to be a time and a place where we can collectively acknowledge the pollution, the poison, the toxicity of practicing clinical detachment in the face of the suffering of other people. And this young man learns the lesson the hard way in the play because he has to make a choice between what he's been ordered to do by his institution and what he knows he should do in accordance with his own moral compass. These are going to be the questions that people are facing in their medical settings and homes all over the country for the months to come. And the one thing that I have seen in doing this work, and it's something I experienced as a caregiver when faced with the suffering of someone I love that I couldn't stop, that I couldn't address, is of feeling helpless in the face of someone we love suffering, that we all feel that we're the only people who've ever felt this alone, this much sorrow, this much anguish. And so the power of Greek tragedy in the ancient amphitheater for 17,000 people is that it has this public health message built directly into it. And you can think it's just an adage or it's some aphorism or something people say this idea "you're not alone." And then you can experience it through a dialogue and an exchange with a group of people who've come together in real time to grapple with the questions that are at the center of his play. And you can see you're not alone in your community. And most critically you can see, by virtue of the fact that we're performing plays that are 2,500 years old, you are not alone across time. And sometimes I think it doesn't really matter if a performance goes well or a discussion goes well, even if we just convey that to people, even if they're just for a moment lifted out of the all-encompassing isolation that's attendant and part of the experience of grief and pain and spiritual anguish that comes with being thrust into these morally complex situations and being asked to make decisions for which there aren't necessarily ever going to be right answers and by which we'll be haunted no matter what we decide to do for the rest of our lives. If we could just convey to people that they're not the only people on the planet who are currently struggling with those questions and that they're not the only people on the planet who have ever struggled with those questions, I think that's the service, that's the public-health message of ancient Greek tragedy.

Host: 29:18

And that was the closing message in both of the performances that I saw. I think very pointedly.

Bryan Doerries: 29:23

It is the closing message. There are a couple others. I mean, it's sort of a double-edged message. You know, the other benediction at the end of our performances is that someone stood up at one of our performances and answered a question I often ask audiences, "Why do you think Sophocles wrote these plays?" And this individual who was a healer and also a general stood up in her community in front of a bunch of other generals and she said, "I think he wrote the plays to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable." And that's really the motto of Theater of War Productions. Can we do both at once? And if it can, can it lift us up out of the isolation of all of those feelings of shame and guilt and being disconnected and isolated, and bring us back into the company of other people who were also struggling with those feelings and connect us. So the second play briefly is about Heracles, or Hercules, and the last day of his life, where he discovers that he's essentially been poisoned accidentally by his wife, Deianira, with a drug given to her by a dying centaur, who had it out for Hercules. So, lesson number one, never trust a dying centaur. That's one of the morals of the story. And ultimately Heracles realizes that he's going to die. And he gathers his 15-year-old son and asks him in the Greek to be his doctor by burning him alive in this ritualized way at the top of Mount Oeta, the Mountain of Zeus. And the son says, "What are you asking me to do, father? Are you asking me to be your murderer and stained with the pollution of your blood and hounded by Furies forever?" And Heracles says, "Do it or be someone else's son." And the son says, "If I am loyal to you, then I'm disloyal to myself and my sense of what is right. Is this the lesson that I'm to learn?"

And so the reason we present this play to medical audiences, just like the other one, is because the question of how do I protect what makes me who I am and my spiritual core and my values as a person and also serve other people in situations in which I may be asked to violate those very things in order to serve them. And I'm not being asked them in some philosophical way over a glass of wine, I'm being asked to do those things in an unfolding emergency that's happening in real time. And I'm having to make split-second decisions that are gonna affect the rest of my life. And I guess the one thing that all of our work seems to address, whether it's the military or medicine or law enforcement or lawyers, is the myth of clinical detachment. And the myth of clinical detachment is—I can compartmentalize these experiences indefinitely and they will not have any effect on me or my practice. And that is a toxic myth and the culture that tells us to silence people when they raise their hand and say, "In fact, that is not the case. And I'm burning out." Is the culture of repression. Is the culture of victim blaming that we are crawling up out of limb by limb as a culture right now. And the question of whether we survive this pandemic and how medicine finds itself when it's over really hinges on whether people begin to process these experiences not years after they happened, but as they're happening. They begin the process of naming it and talking about it and giving voice to it and collectively mourning it while going about their practice. And that's the challenge at the center of these plays, the center of the exchanges we have, but it's our contention that it makes better physicians, better nurses, better healthcare professionals if they're given the opportunity and empowered to communalize these experiences in healthy ways, even while they're happening.

Host: 33:35

You've touched on this next question in so many different ways, but I kind of want to have you pull some of the threads together. What has your work taught you about communal resilience?

Bryan Doerries: 33:47

Look, I don't think, I think one of the other myths of the 20th century is that people heal in closed rooms, one-on-one. I'm not saying that that doesn't work. The jury is still out on all of that. And there are certainly things like cognitive behavioral therapy and exposure therapy. I know there's evidence those things work. But even if they do, only five percent of us make it into a clinical setting. Five percent of us. So what about the 95 percent of us who never make it in for whatever series of reasons? Our religion, the fact that we live in a health care desert—.

Host: 34:25

Price.

Bryan Doerries: 34:25

Price, stigma. I mean there's so many reasons where we don't. So while we're waiting to create an equitable society where everyone has access to mental health care, we should be thinking about ways to engage large groups of people in the communalization of these moral and spiritual and psychological questions. And the Greeks had a model for it. They developed a form of storytelling. And I really don't care if people want to be engaged with the Greek myths after these things are over. That's why I don't care about the pronunciations. That's why you could switch the stories of any culture into the model and it still works as we've done in Japan with Japanese noh plays, or we've done in other parts of the world with their traditions. It's the platform of bringing people together and creating a space where we see and hear in both directions and where we're invited and empowered to reflect upon what we see of ourselves in ancient stories. And I think, you know, it's Veteran's Day today while we're recording this. I know it won't be when it's released, but it's November 11th and it's not lost on me that these Greek plays really were, I think, the public health message was even more specific for that ancient audience. It's not: "Hey, you veteran, you shoulder the pollution of what you've seen or experienced on your own in isolation, in your car or your closet or your bathroom." It's: "We will collectively shoulder the pollution of what you've brought back from the war as a community. Not just those of us who went to war, but those who didn't go to war. And it's incumbent upon those who didn't go to war to be part of that process, because even if we try to avoid it, the blood is already on our hands. The blood of the people who've returned from the war whom we relegate and ignore because they speak the truth of the traumas that they've experienced on our behalf. So we have to wake up to our own moral injury of practicing clinical detachment from the very suffering that we're complicit in causing not just to our neighbors and friends, but all around the world.

We are sicker as civilians and in need of healing as much if not more than these populations we think of as traumatized. And until we get down into the muck with them and acknowledge our own moral ambivalence and failings and struggles, we will be also sick if not sicker than they are. And so that ability to create spaces where people can acknowledge their own moral suffering alongside, because the other myth that we're here to dispel, almost everyone who's experienced trauma that we've encountered often espouses the attitude that no one can understand my experience except the people who were in the same place at the same time that whatever traumatizing thing occurred happened. And, yes, that's true, we cannot understand the material circumstances of each other's—what led to the trauma. But we can understand the feeling of isolation. We can understand the feeling of anguish. We can feel the feeling of abandonment or betrayal, because there are so many roads to that same place. And so sometimes in our performances, we have people standing up and saying, "I'm not a veteran, I'm not a doctor, but I was kidnapped as a child," or "I was sexually assaulted by someone in my family." Whatever the series of things is, and they, just by virtue of the bravery of acknowledging that they may not understand the material circumstances of the person who spoke before them, but they understand at some basic intrinsic level, the feeling of isolation. I think that's how we heal as groups. And that's why it can't be done in isolation between two people, not exclusively. And when we relegate people to their cars and closets and, yes, even to clinical spaces, to have those conversations, we are also distancing ourselves morally from the things those people might say in our presence that might implicate us in their suffering.

Host: 38:42

And it leads again, it seems to me, to the final point of you are not alone.

Bryan Doerries: 38:46

Absolutely. And that's it, right? I mean, you can hear it and it sounds pithy. And then you can experience it and realize it for yourself. Pain, anguish, spiritual suffering, moral distress are just intrinsically isolating experiences. They're so all-consuming. The pain often is so all-consuming that we can't see out of it. We're on our own islands like Philoctetes. And on Zoom we're in our own little boxes. And we're actually not physically able to break out of these boxes on Zoom, which I think is a perfect metaphor for the characters in Greek tragedy. Something metaphysical, something spiritual, something that goes beyond the material limits of our existence has to occur if we're to get off these islands. And even if it doesn't occur in the moment, the stretching of our imagination, of our powers of perception, of our willingness to be uncomfortable together in a space, I would contend leads to the possibility of getting out of the box. It doesn't have to happen immediately. I don't see Theater of War Productions' work as therapy. I don't see it as therapeutic. I would never contend that it's the fix for everybody. It's a door. And whether you walk out of your box through that door or off your Island into a path of healing or connection, that's really up to you.

Host: 40:17

Bryan Doerries is a writer, translator, director and the artistic director of Theater of War Productions. As I mentioned at the beginning, Theater of War is doing a special performance for front-line medical providers over Zoom on Thursday, November 19th at 7PM Eastern. The event is hosted by Mount Sinai, but it's free and open to the public. Just make sure to reserve your tickets. You can do that by following the link in the show notes. If you enjoyed this episode, please rate and review Road to Resilience on Apple Podcasts. It helps other people find the show. And sign up for our newsletter. It comes out once a month. Road to Resilience is a production of the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. It's made by Katie Ullman, Nicci Hudson, and me, Jon Earle. Lucia Lee is our Executive Producer. From all of us here, thank you so much for listening. We'll see you next time.