The Mystery Virus

Date Published: March 8, 2019

In 1977, Doug Dieterich, MD contracted a mysterious virus that attacked his liver and left him unable to work. Four decades later, Dr. Dieterich, Director of the Institute for Liver Medicine at The Mount Sinai Hospital, reflects on his journey from patient to caregiver with the help of an unlikely ally—AIDS activist and “cockney rebel” Leigh Blake—and explains why Hepatitis C isn’t the terrifying diagnosis it once was.

Dr. Dieterich and Leigh explain how they turned their diagnosis into positive action. “I’ve always felt that when pain comes, you have to use it,” Leigh says, “That’s what it’s designed for.” Leigh’s hepatitis C diagnosis inspired her to expand her humanitarian work, thereby saving thousands of lives affected by HIV/AIDS, while Dr. Dieterich’s diagnosis inspired him to become a renowned liver specialist.

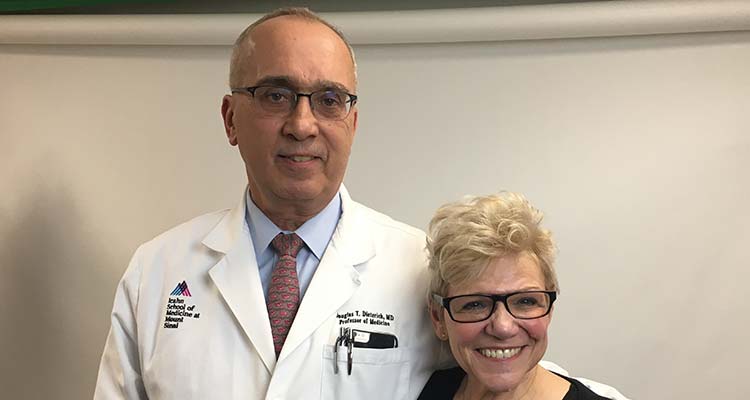

Dr. Douglas Dieterich and patient Leigh Blake

Leigh Blake, Mount Sinai Patient

Podcast Transcript

Host: 00:00

You're listening to Road to Resilience. I'm Jon Earle. Our story today begins with a teeny, tiny, pinch. A very small accident that had big consequences. It was the summer of 1977, Doug Dieterich had just finished his third year of medical school. He was studying to become an ophthalmologist. That summer, he was working at a veteran's hospital in New York City.

Dr. Dieterich: 00:27

I stuck myself with a needle from a guy who was really dying of liver disease. I was like, Oh s**t, I think I'm in trouble.

Host: 00:33

He went to the emergency room, got a big shot of antibodies, but it didn't stop this mystery virus.

Dr. Dieterich: 00:38

I got really sick. I was exhausted and I looked in the mirror and my eyes were like bright yellow. So I was really in bad shape.

Host: 00:47

For two months, Doug couldn't do anything. He couldn't work. He definitely couldn't go back to school. All he could do was try to hang on. Even though the virus that was attacking his liver, there was no treatment for it. Zero. It didn't even have a name. And somehow through all that fear and exhaustion, Doug made a decision that changed his life. He decided to fight back.

Dr. Dieterich: 01:08

Gradually I sort of got mad I guess at the virus and I said, dammit, it's like we need to do something about this. You know, it's like going into ophthalmology and taking out of cataracts is probably not going to help anybody with this disease. So I decided to change gears and go into GI and liver disease.

Host: 01:27

Doug decided to become a liver specialist in the hope that someday he would be able to cure himself and others. The alternative was grim. If he failed, he could end up like that man at the VA dying of liver disease. The mystery virus that made Dr. Dieterich so sick was known at the time as "non-A, non-B hepatitis." Today we call it hepatitis C. We're devoting this episode of Road to Resilience to hep C for a really good reason, and it's that hep C kills more Americans than any other infectious disease, more even than HIV. HIV! On this episode, we'll go back to the battle days of hep C treatment and talk about the breakthrough that changed everything.

Dr. Dieterich: 02:11

Their were gasps in the audience and the analysts, you can see them running for the phones.

Host: 02:16

We'll touch on the connection between hep C and the opioid crisis.

Dr. Dieterich: 02:19

The last two rows of graves, they were all young people.

Host: 02:23

And we'll meet the punk provocateur who also turned her hep C diagnosis into a mission to help others.

Leigh Blake: 02:29

I never sit on pain. I always use it, because that's what it's for.

Host: 02:33

That's all coming up next on Road to Resilience. Before we go any further, we need to talk about hep C itself.

PSA: 02:39

Left untreated, Hepatitis C can destroy your liver over time, possibly leading to fibrosis, cirrhosis, liver cancer, or death.

Host: 02:51

Okay. So that's all true, but let's take it down just a notch. Here are the facts. Hep C is a virus that attacks the liver. It's transmitted by blood. Today, that mostly means sharing dirty needles. But before 1992 when people started screening for it, you could get hep C through blood transfusions and organ transplants. That's why some people mistakenly think of it as a baby boomer disease. But the thing that really blew my mind when I was researching for this show is that hep C is so, so common. The CDC estimates that 2.4 million Americans have hep C. That's about one percent of the adult population. And because chronic hep C often doesn't show any symptoms, half of those people don't even know it. And you know how I said a moment ago that lots of people think of hep C as a baby boomer disease? Well, maybe at a certain point that was kind of true, but it's really changing fast. And that's because of the opioid crisis. With so many people using injection drugs, acute infections of hep C among young people especially are way, way up.

Dr. Dieterich: 03:51

One of our offices in New Jersey, when I was out there a few months ago and it's right next to a cemetery and I saw the last two rows of graves with their pictures. They were all young people all dead from heroin overdoses.

Host: 04:06

But before you freak out, you should know that hep C is curable. We'll get to that later in the show, but now it's time to meet Leigh Blake, the irrepressible unstoppable, Leigh Blake. Tell me a little bit about where you're from.

Leigh Blake: 04:21

Oh, I'm from the projects in London, in South London. My parents both worked on London Underground. My mother was a ticket collector and my father was a station man at Charing Cross Station. And he ran the racism cases in the union. So that's what I grew up with, with a real incredible sense of what justice meant. And I think that's why I am who I am primarily is because of my father's activist leanings. But I was also lucky enough to grow up at a time of swinging London. We were cutting our hair in shapes and we had long boots and we were running around in this union jack outfitted cultural explosion.

Host: 05:16

Leigh loved music. I don't know, I think in the way that only teenagers can love it. It was everything to her. It was her whole identity and it went way beyond hanging a poster in a room.

Leigh Blake: 05:25

I left school when I was—actually, I was thrown out of school when I was 15 for being on tour with The Who all the time.

Host: 05:33

And a few years later she befriended David Byrne, front man for an up and coming band called The Talking Heads. David introduced her to the New York art scene.

Leigh Blake: 05:42

You know, I met Andy Warhol who said to me, "Oh my God, Leigh." He said, "I love your band Talking Horses." And I went to David I was like, "We have to rename the band Talking Horses!" And he was like, "No, we're not going to do that, but I get you."

Host: 05:58

So to be clear, Leigh wasn't a member of The Talking Heads. She was, and these are her words, the "ultra fashionable English girl they took everywhere." Leigh spent the 1980s playing in a punk band, managing artists, making films, and of course hanging out with the coolest people in the world. Patti Smith, The Ramones, Jean-Michel Basquiat. And then AIDS hit and the party came crashing down.

Leigh Blake: 06:21

I remember the moment where I was completely horrified about HIV/AIDS and that was, I was in the West Village and I saw this man walk toward me who was like a walking skeleton. He was covered in Kaposi's marks and he yelled out to me, "Leigh!" I didn't recognize this man. I'd never seen this man before in my life. And then I realized, Oh my God, I actually do know this man. This man is a shadow of the man that he was when I knew him. And we went and had coffee and we sat down and he told me the whole story of how he's been treated and it was horrible and that's when I was completely galvanized.

Host: 07:07

Leigh became an AIDS activist. She realized she could harness pop culture to fight the disease. Leigh asked some music industry friends to record an AIDS benefit album called Red Hot and Blue. It was a compilation of Cole Porter songs performed by stars like U2 and Annie Lennox. And it sold over a million copies worldwide. But Leigh didn't stop there. With the money she raised, Leigh built a clinic for children with HIV/AIDS in Kenya. The clinic provided nutrition, vaccinations and antibiotics, but it couldn't provide the one thing that the children really needed - lifesaving anti-retroviral drugs. In the early 2000s, they were too expensive. For Leigh, not being able to provide those drugs was really frustrating, it was heartbreaking. And while she was wrestling with this problem, she got a serious diagnosis of her own.

Leigh Blake: 08:05

I didn't realize that something wasn't right with my health. I just had routine lab tests and my doctor asked me was I drinking last night? And he said, oh cause your liver enzymes are high. I was like, okay, well no idea and that's where I learned I was positive. I don't know where I got Hepatitis C from. I did live a druggie existence in the 80s I had a couple of the wrong boyfriends.

Host: 08:33

What was your reaction when you got that news?

Leigh Blake: 08:35

You know, all I could think about was my son who was about two. Was I going to see him grow up? Was I going to die and lose the beauty of mothering? I'd had five miscarriages and managed to have a baby finally. He was my little miracle. Was I gonna survive?

Host: 08:55

Leigh's path to health was far from clear. The hep C treatments available at the time, and this is around the year 2000, were still really primitive by today's standards. They involved injections and pills and they had these terrible side effects like nausea. And way too often, they didn't work, but the alternative was even worse.

PSA: 09:14

Cirrhosis, liver cancer or death.

Host: 09:16

We're stuck between a rock and liver disease. Leigh drew on a philosophy she developed during her years of activism and found the strength to fight on.

Leigh Blake: 09:27

I've always felt that when pain comes, it's a test of your integrity, it's a test of your possibilities and you have to use it. That's what it's designed for.

Host: 09:44

While Leigh searched for a cure for her hep C, a search that would last years, she turned her pain into service. She poured herself into her HIV/AIDS work. And then came the moment that changed her life again.

Leigh Blake: 09:57

One day a woman came into that clinic called Anne and her boy was Brian and he was three and he was very close to dying. And it really moved me because I'd just been diagnosed with hep C and I really didn't know what it was and I remember thinking all the time, I'm not going to see my son grow up. And when this woman walked into this clinic and felt the same way that I did, I took the symbolism of that and I said, I'll pay for those drugs.

Host: 10:30

Just as a chance encounter in the West Village had galvanized her to fight HIV/AIDS, Anne's story inspired Leigh to expand her activism. She started organizing showbiz friends to pay for lifesaving drugs for children. And in 2003, she and singer Alicia Keys founded Keep a Child Alive. Together they raised millions of dollars for HIV/AIDS relief and saved, by her estimate, hundreds of thousands of lives.

Leigh Blake: 10:56

I think that's what I'm most proud of, that I took that moment when it was presented to me by the universe and used it. That I used my pain and my own particular fear.

Host: 11:08

After being diagnosed with hep C in 2000, Leigh spent years searching for a doctor and a treatment plan that she was comfortable with. Like many people with chronic hep C, she didn't feel sick, but she knew if she didn't treat it, the virus could kill her. She had friends who died from the disease because they felt fine and just never got around to treating it. So Leigh went from doctor to doctor, doctor to doctor.

Leigh Blake: 11:32

The first doctor I went to... the second doctor I went to got my viral loads wrong. The third doctor I went to, it just was too, was also in this old school, old frame of treatment.

Host: 11:41

Until finally...

Leigh Blake: 11:42

And then I found Dr. D and I walked in and I thought, I love this man already. Like, I really love this man already.

Host: 11:54

What was it about him that you loved?

Leigh Blake: 11:56

He's awake. He's awake to who you are. He's awake to how you're feeling. And he knew what that old treatment felt like, so he wasn't going to put his patients through it because he'd been through it himself.

Host: 12:09

Doug Dieterich, now, Dr. Dieterich, a liver specialist at The Mount Sinai Hospital, really had been through it. When we left off with Dr. Dieterich, he was a medical student suffering from an acute hep C infection. After a few months, his symptoms - the yellow face, the exhaustion - disappeared on their own. He didn't feel sick anymore and his liver numbers basically returned to normal, which happens with hep C. So Dr. Dieterich returned to medical school, graduated and went on to do an internship and residency at Bellevue Hospital here in New York. There likely, he got involved in the fight against HIV/AIDS, working as a researcher. As for his hep C well, it was just sort of there in the background. It was damaging his liver, but it wasn't making him feel sick. And since there were no real treatment options available in the 1980s, he sort of put it on the back burner, but he kept his ear to the ground. Over a decade after Dr. Dieterich pricked himself with a dirty needle, the Hepatitis C virus was finally identified and in the very early 1990s, Dr. Dieterich enrolled in one of the first clinical trials for a hep C drug.

Dr. Dieterich: 13:14

That was miserable. You know, it's like one of our patients has described that as like 12 months of PMS with cold. Terrifyingly awful side effects, fevers, chills, insomnia, you know, it's like, it's really difficult.

Host: 13:27

So when Leigh says that Dr. Dieterich had been through it with hep C, he really, really had. Remember, it's the reason why he became a liver doctor in the first place and it turns out it made him a better doctor because he could empathize with patients like Leigh who were scared.

Leigh Blake: 13:42

When you are positive for hep C, you live in a lot of fear, you start to let you get itches. You start to think, oh my liver's failing. You know, you go through a lot of made up fear and he helped me understand all that was just nonsense.

Host: 13:56

Dr. Dieterich offered Leigh the better option she'd spent years searching for. He enrolled her in a clinical trial. By this time in the late 2000s, early 2010s, the drugs had improved since that trial that had failed to cure Dr. Dieterich, but the treatment was still no walk in the park. More injections, more pills, severe side effects. Sometimes it got so bad that Leigh wanted to quit. It was Dr. Dieterich who helped her stick it out.

Leigh Blake: 14:22

I had to go to India with my work halfway through my treatment. Finding a fridge to keep this stuff code for the injections was like crazy. It was 115 degrees and I was shooting up with these medicines and I said to Dr. Dieterich, can I stop? And he was like, no, you can't. And I was like, uhhh.

Host: 14:47

Leigh stayed resilient and strong. She trusted Dr. Dieterich and her determination paid off. The clinical trial worked and she was cured of Hepatitis C. We've talked a lot about the old regime of hep C treatment, the pills and the injections, the terrible side effects. What you need to know is that things are very, very different now. Over the past decade, new classes of drugs have appeared that cure hep C within a matter of weeks and with almost no side effects. It all started with a breakthrough one Sunday afternoon in late 2011. The place was San Francisco. The event was the 62nd annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, also known as the liver meeting. From 6:30 AM to 9:00 PM nothing but livers. One of those presentations was by a Hepatologist, a liver doctor from New Zealand named Dr. Ed Gane. Dr. Gane had been researching hep C's since the early 1990's. His presentation that day was about a clinical trial. Dr. Dieterich was there.

Dr. Dieterich: 15:48

He had like four arms, you know, Interferon, Ribavirin and Sofosbuvir. Three drugs...

Host: 15:53

What Dr. Gane was showing in this very dramatic way was that you could substitute the old, scary hep C drugs for this new drug. And when you did that, the side effects went completely away, and more importantly, the cure rate went to 100 percent.

Dr. Dieterich: 16:07

100 percent. So it was a dramatic moment. There were gasps in the audience, and the analysts, you can see them running for the phones because it was so spectacular. I mean that was one of those like sort of once in a lifetime, a blowout advances.

Host: 16:23

Thanks in large part to that discovery, hep C is now easy to cure.

Dr. Dieterich: 16:26

Nowadays it's eight weeks for three bills a day, 12 weeks for one pill a day, and we're 99-percent cure rate.

Leigh Blake: 16:34

Easy, peasy, lemon squeezy.

Dr. Dieterich: 16:35

It's amazing. I mean it's really amazing now.

Host: 16:38

So what's the message now?

Dr. Dieterich: 16:40

I think it's, I mean you shouldn't be afraid of Hepatitis C or or getting a positive result. There's no stigma. Just get tested and get treated because we can cure 99 percent with virtually no side effects.

Leigh Blake: 16:50

You can do it, or you can have a decade or more taken off your life. That doesn't seem like a good deal to me. For eight weeks.

Host: 16:59

Today, almost 20 years after a Kenyan mother named Anne walked into her clinic, Leigh Blake is still fighting for moms. Her newest initiative is called Fund a Mom and it's aimed at lifting Indian mothers out of extreme poverty. We'll put a link in the show notes. Her son, India Blue Sebastian, is now 20 and he's followed his mother into the music business rapping under the name SaddiqThaKidd. Dr. Dieterich is Director of the Institute of Liver Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine, hep C-free since the late 1990s, he helps patients like Leigh tackle their fears and get cured the easy way. That's it for this episode of Road to Resilience. Thank you so much Leigh and Dr. Dieterich for sharing your story with us. You guys are seriously the best. Thanks also to Katie Ullman and Nicci Hudson for your help on this episode. Road to Resilience is a production of the Mount Sinai Health System. If you liked what you've heard on this episode, subscribe to us on iTunes and rate us. It helps other listeners find the show. You can also email us at podcasts@mountsinai.org. I'm Jon Earle. See you next month with more resilience stories.

Leigh Blake: 18:14

All I can say to you about Dr. Dieterich is that he's just my favorite person on earth. I mean he and Bono are like a bit of... they're fighting each other for my affections internally.