Cyanotic heart disease

Right-to-left cardiac shunt; Right-to-left circulatory shunt

Cyanotic heart disease refers to a group of many different heart defects that are present at birth (congenital). They result in a low blood oxygen level. Cyanosis refers to a bluish color of the skin and mucous membranes.

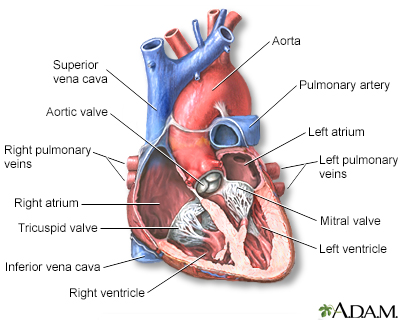

The interior of the heart is composed of valves, chambers, and associated vessels.

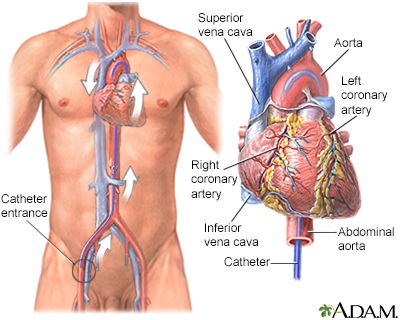

Cardiac catheterization is used to study the various functions of the heart. Using different techniques, the coronary arteries can be viewed by injecting dye or opened using balloon angioplasty. The oxygen concentration can be measured across the valves and walls (septa) of the heart and pressures within each chamber of the heart and across the valves can be measured. The technique can even be performed in small, newborn infants.

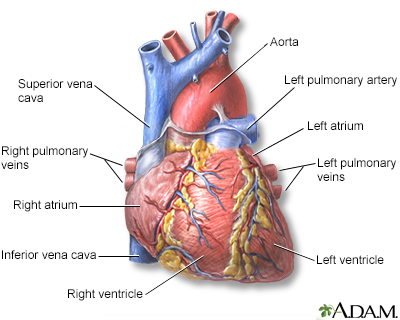

The external structures of the heart include the ventricles, atria, arteries and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart while veins carry blood into the heart. The vessels colored blue indicate the transport of blood with relatively low content of oxygen and high content of carbon dioxide. The vessels colored red indicate the transport of blood with relatively high content of oxygen and low content of carbon dioxide.

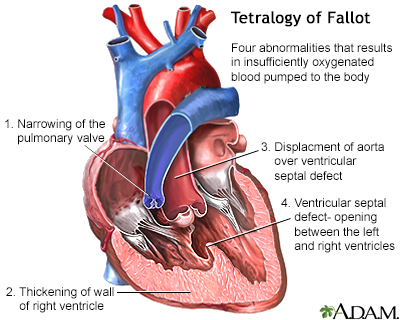

Tetralogy of Fallot is a birth defect of the heart consisting of four abnormalities that results in insufficiently oxygenated blood pumped to the body. It is classified as a cyanotic heart defect because the condition leads to cyanosis, a bluish-purple coloration to the skin, and shortness of breath due to low oxygen levels in the blood. Surgery to repair the defects in the heart is usually performed between 3 and 5 years old. In more severe forms, surgery may be indicated earlier. In most cases the heart can be surgically corrected and the outcome is good.

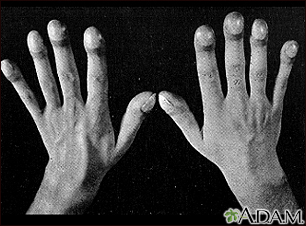

Clubbing may result from chronic low blood-oxygen levels. This can be seen with cystic fibrosis, congenital cyanotic heart disease, and several other diseases. The tips of the fingers enlarge and the nails become extremely curved from front to back.

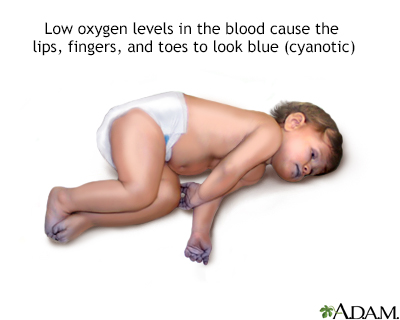

Cyanotic heart disease is a congenital heart defect which results in low oxygen levels in the blood and causes the child's lips, fingers, and toes to look blue (cyanosis).

Causes

Normally, blood returns from the body and flows through the heart and lungs.

- Blood that is low in oxygen returns from the body to the right side of the heart.

- The right side of the heart then pumps the blood to the lungs, where it picks up more oxygen and becomes red.

- The oxygen-rich blood returns from the lungs to the left side of the heart. From there, it is pumped to the rest of the body.

Heart defects that children are born with can change the way blood flows through the heart and lungs. These defects can cause less blood to flow to the lungs. They can also result in blue and red blood mixing together. This causes poorly oxygenated blood to be pumped out to the body. As a result:

- The blood that is pumped out to the body is lower in oxygen.

- Less oxygen delivered to the body can make the skin look blue (cyanosis).

Some of these heart defects involve the heart valves. These defects force blue blood to mix with red blood through abnormal heart channels. Heart valves are found between the heart and the large blood vessels that bring blood to and from the heart. These valves open up enough for blood to flow through. Then they close, keeping blood from flowing backward.

Heart valve defects that can cause cyanosis include:

- Tricuspid valve (the valve between the 2 chambers on the right side of the heart) may be absent or unable to open wide enough.

- Pulmonary valve (the valve between the heart and the lungs) may be absent or unable to open wide enough.

- Aortic valve (the valve between the heart and the blood vessel to the rest of the body) is unable to open wide enough.

- Mitral valve (the valve between the 2 chambers on the left side of the heart) may be absent or unable to open wide enough. This is very rare and a poorly formed left ventricle may also be present.

Other heart defects may include abnormalities in valve development or in the location and connections between blood vessels. Some examples include:

- Coarctation or complete interruption of the aorta

- Ebstein anomaly

- Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Total anomalous pulmonary venous return

- Transposition of the great arteries

- Truncus arteriosus

Certain medical conditions in the mother can increase the risk of certain cyanotic heart diseases in the infant. Some examples include:

- Chemical exposure

- Genetic and chromosomal syndromes, such as Down syndrome, trisomy 13, Turner syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and Noonan syndrome

- Infections (such as rubella) during pregnancy

- Poorly controlled blood sugar level in women who have diabetes during pregnancy

- Medicines prescribed by your health care provider or bought on your own and used during pregnancy

- Street drugs used during pregnancy

Symptoms

Some heart defects cause major problems right after birth.

The main symptom of cyanosis is a bluish color of the lips, fingers, and toes that is caused by the low oxygen content in the blood. It may occur while the child is resting or only when the child is active.

Some children have breathing problems (dyspnea). They may get into a squatting position after physical activity to relieve breathlessness.

Others have spells, in which their bodies are suddenly starved of oxygen. During these spells, symptoms may include:

- Anxiety

- Breathing too quickly (hyperventilation)

- Sudden increase in bluish color to the skin

Infants may get tired or sweat while feeding and may not gain as much weight as they should.

Fainting (syncope) and chest pain may occur.

Other symptoms depend on the type of cyanotic heart disease, and may include:

- Feeding problems or reduced appetite, leading to poor growth

- Bluish color to the skin (cyanosis) due to low oxygen level in the blood

- Puffy eyes or face

- Tiredness all the time

Exams and Tests

Physical examination confirms cyanosis. Older children may have clubbed fingers.

The provider will listen to the heart and lungs with a stethoscope. Abnormal heart sounds, a heart murmur, and lung crackles may be heard.

Tests will vary depending on the cause, but may include:

- Chest x-ray

- Checking oxygen level in the blood using an arterial blood gas test or by checking it through the skin with a pulse oximeter

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- ECG (electrocardiogram)

- Looking at the heart structure and blood vessels using echocardiogram or MRI of the heart

- Passing a thin flexible tube (catheter) into the right or left side of the heart, usually from the groin (cardiac catheterization)

- Transcutaneous oxygen monitor (pulse oximeter)

- Echo-Doppler

Treatment

Some infants may need to stay in the hospital after birth so they can receive oxygen or be put on a breathing machine. They may receive medicines to:

- Get rid of extra fluids

- Help the heart pump harder

- Keep certain blood vessels open

- Treat abnormal heartbeats or rhythms

The treatment of choice for most congenital heart diseases is surgery to repair the defect. There are many types of surgery, depending on the kind of birth defect. Surgery may be needed soon after birth, or it may be delayed for months or even years. Some surgeries may be staged as the child grows.

Your child may need to take water pills (diuretics) and other heart medicines before or after surgery. Be sure to follow the correct dosage. Regular follow-up with the provider is important.

Many children who have had heart surgery must take antibiotics before, and sometimes after having any dental work or other medical procedures. Make sure you have clear instructions from your child's heart provider.

Ask your child's provider before getting any immunizations. Most children can follow the recommended guidelines for childhood vaccinations.

Outlook (Prognosis)

The outlook depends on the specific disorder and its severity.

Possible Complications

Complications of cyanotic heart disease include:

- Abnormal heart rhythms and sudden death

- Long-term (chronic) high blood pressure in the blood vessels of the lung

- Heart failure

- Infection in the heart

- Stroke

- Death

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if your baby has:

- Bluish skin (cyanosis) or grayish skin

- Breathing difficulty

- Chest pain or other pain

- Dizziness, fainting, or heart palpitations

- Feeding problems or reduced appetite

- Fever, nausea, or vomiting

- Puffy eyes or face

- Tiredness all the time

Prevention

Some inherited factors may play a role in congenital heart disease. Many family members may be affected. If you are planning to get pregnant, talk to your provider about screening for genetic diseases.

Women who plan to become pregnant should be immunized against rubella if they are not already immune. Rubella infection in a pregnant woman can cause congenital heart disease.

Women who are pregnant should get good prenatal care:

- Avoid alcohol and illegal drugs during pregnancy.

- Tell your provider that you are pregnant before taking any new medicines.

- Have a blood test early in your pregnancy to see if you are immune to rubella. If you are not immune, avoid any possible exposure to rubella and get vaccinated right after delivery.

- Pregnant women who have diabetes should try to get good control over their blood sugar level.

References

Bernstein D. Cyanotic congenital heart disease: evaluation of the critically ill neonate with cyanosis and respiratory distress. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, MBBS, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 456.

Lange RA, Cigarroa JE. Congenital heart disease. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, Heidelbaugh JJ, Lee EM, eds. Conn's Current Therapy 2023. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:110-115.

Valente AM, Dorfman AL, Babu-Narayan SV, Kreiger EV. Congenital heart disease in the adolescent and adult. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 82.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 10/23/2023

Reviewed by: Michael A. Chen, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.