Meningitis - gram-negative

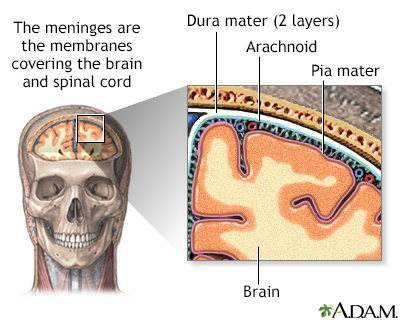

Meningitis is an infection of the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. This covering is called the meninges.

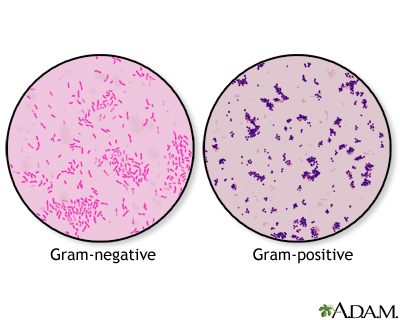

Bacteria are one type of germ that may cause meningitis. Gram-negative bacteria are a type of bacteria that behave in a similar manner in the body. They are called gram-negative because they turn pink when tested in the lab with a special stain called Gram stain.

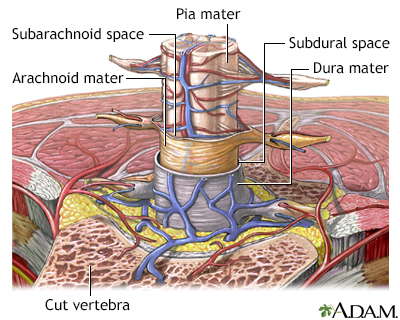

The organs of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) are covered by connective tissue layers collectively called the meninges. Consisting of the pia mater (closest to the CNS structures), the arachnoid and the dura mater (farthest from the CNS), the meninges also support blood vessels and contain cerebrospinal fluid. These are the structures involved in meningitis, an inflammation of the meninges, which, if severe, may become encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain.

The organs of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) are covered by 3 connective tissue layers collectively called the meninges. Consisting of the pia mater (closest to the CNS structures), the arachnoid and the dura mater (farthest from the CNS), the meninges also support blood vessels and contain cerebrospinal fluid. These are the structures involved in meningitis, an inflammation of the meninges, which, if severe, may become encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain.

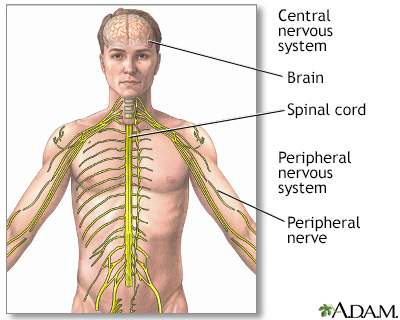

The central nervous system comprises the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system includes all peripheral nerves.

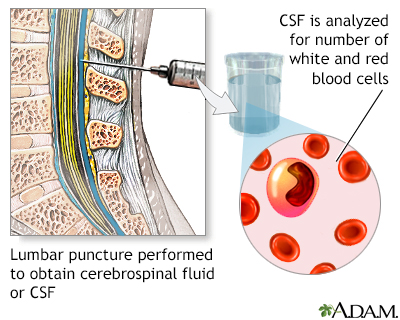

CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) is a clear fluid that circulates in the space surrounding the spinal cord and brain. A CSF cell count is a test to measure the number of red and white blood cells that are in CSF.

A Gram stain is a test used to help identify bacteria. The tested sample can be taken from body fluids that do not normally contain bacteria, such as blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid. A sample can also be taken from the site of a suspected infection, such as the throat, lungs, genitals, or skin. Bacteria are classified as either Gram-positive or Gram-negative, based on how they color in reaction with the Gram stain. The Gram stain is colored purple. When combined with the bacteria in a sample, the stain will either stay purple inside the bacteria (Gram-positive), or it will turn pink (Gram-negative). Examples of Gram-positive bacteria include Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as bacteria that cause anthrax, diphtheria, and toxic shock syndrome. Examples of Gram-negative bacteria include Escherichia coli (E coli), Salmonella, Hemophilus influenzae, as well as many bacteria that cause urinary tract infections, pneumonia, or peritonitis.

Causes

Acute bacterial meningitis can be caused by different Gram-negative bacteria including meningococcus and H influenzae.

This article covers Gram-negative meningitis caused by the following bacteria:

- Escherichia coli

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Serratia marcescens

Gram-negative meningitis is more common in infants than adults. But it can also occur in adults, especially those with one or more risk factors. Risk factors in adults and children include:

- Infection (especially in the abdomen or urinary tract)

- Recent brain surgery

- Recent injury to the head

- Spinal abnormalities

- Spinal fluid shunt placement after brain surgery

- Urinary tract abnormalities

- Urinary tract infection

- Weakened immune system

Symptoms

Symptoms usually come on quickly, and may include:

- Fever and chills

- Mental status changes

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Severe headache

- Stiff neck (meningismus)

- Symptoms of a bladder, kidney, intestine, or lung infection

Other symptoms that can occur with this disease:

- Agitation

- Bulging fontanelles in infants

- Decreased consciousness

- Poor feeding or irritability in children

- Rapid breathing

- Unusual posture, with the head and neck arched backwards (opisthotonos)

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam. Questions will focus on symptoms and possible exposure to someone who might have the same symptoms, such as a stiff neck and fever.

If your provider thinks meningitis is possible, a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) will likely be done to remove a sample of spinal fluid for testing.

Other tests that may be done include:

- Blood culture

- Chest x-ray

- CT scan of the head

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Gram stain or, other special stains, and culture of the spinal fluid

Treatment

Antibiotics will be started as soon as possible. Ceftriaxone and cefepime are the most commonly used antibiotics for this type of meningitis. Other antibiotics may be given, depending on the type of bacteria.

If you have a spinal shunt, it may be removed.

Outlook (Prognosis)

The earlier treatment is started, the better the outcome.

Many people recover completely. But, many people have permanent brain damage or die of this type of meningitis. Young children and adults over age 50 have a higher risk for death. How well you do depends on:

- Your age

- How soon treatment is started

- Your overall health

Possible Complications

Long-term complications may include:

- Brain damage

- Buildup of fluid between the skull and brain (subdural effusion)

- Buildup of fluid inside the skull that leads to brain swelling (hydrocephalus)

- Hearing loss

- Seizures

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call 911 or the local emergency number or go to an emergency room if you suspect meningitis in a young child who has the following symptoms:

- Feeding problems

- High-pitched cry

- Irritability

- Persistent unexplained fever

Meningitis can quickly become a life-threatening illness.

Prevention

Prompt treatment of related infections may reduce the severity and complications of meningitis.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Meningitis. About bacterial meningitis.

Nath A. Meningitis: bacterial, viral, and other. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 381.

Hasbun R, Van de Beek D, Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR. Acute meningitis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 87.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 8/29/2024

Reviewed by: Jatin M. Vyas, MD, PhD, Professor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Associate in Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.