Ventriculoperitoneal shunting

Shunt - ventriculoperitoneal; VP shunt; Shunt revision

Ventriculoperitoneal shunting is surgery to treat excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the cavities (ventricles) of the brain (hydrocephalus).

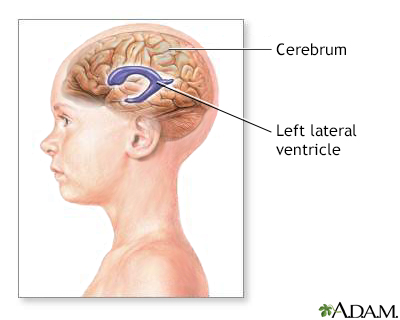

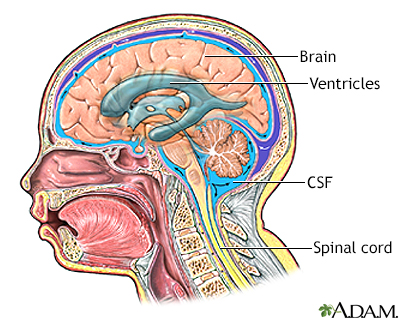

The ventricles of the brain are hollow chambers filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which supports the tissues of the brain.

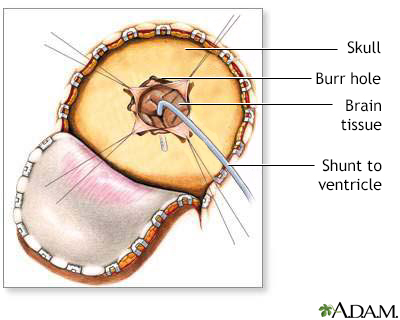

During a cerebral shunt procedure a flap is cut in the scalp and a small hole is drilled in the skull. A small catheter is passed into a ventricle of the brain. A pump (valve which controls flow of fluid) is attached to the catheter to keep the fluid away from the brain. The accumulation of excess fluid around the brain can cause an increase in intracranial pressure. The excess pressure can cause a decrease in blood flow to the brain leading to brain damage.

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) bathes the brain and spinal cord. Most of the CSF is in the ventricles of the brain, which are large cavities within the brain which produce and reabsorb the CSF.

Description

This procedure is done in the operating room under general anesthesia. It takes about 1 1/2 hours. A thin tube (catheter) is passed from the cavities of the head to the abdomen to drain the excess CSF. A pressure valve and an anti-siphon device ensure that just the right amount of fluid is drained.

The procedure is done as follows:

- An area of hair on the head is shaved. This may be behind the ear or on the top or back of the head.

- The surgeon makes a skin incision behind the ear. Another small surgical cut is made in the belly.

- A small hole is drilled in the skull. One end of the catheter is passed into a ventricle of the brain. This can be done with or without a computer as a guide. It can also be done with an endoscope that allows the surgeon to see inside the ventricle.

- A second catheter is placed under the skin behind the ear. It is sent down the neck and chest, and usually into the belly area. Sometimes, it stops at the chest area. In the belly, the catheter is often placed using an endoscope. The surgeon may also make a few more small cuts, for instance in the neck or near the collarbone, to help pass the catheter under the skin.

- A valve is placed underneath the skin, usually behind the ear. The valve is connected to both catheters. When extra pressure builds up around the brain, the valve opens, and excess fluid drains through the catheter into the belly or chest area. This helps lower intracranial pressure. A reservoir on the valve allows for priming (pumping) of the valve and for collecting the CSF if needed.

- The person is taken to a recovery area and then moved to a hospital room.

Why the Procedure Is Performed

This surgery is done when there is too much CSF in the brain and spinal cord. This is called hydrocephalus. It causes higher than normal pressure on the brain. It can cause brain damage.

Children may be born with hydrocephalus. It can occur with other birth defects of the spinal column or brain. Hydrocephalus can also occur in older adults.

Shunt surgery should be done as soon as hydrocephalus is diagnosed. Alternative surgeries may be proposed. Your doctor can tell you more about these options.

Risks

Risks of anesthesia and surgery in general are:

- Reactions to medicines or breathing problems

- Bleeding, blood clots, or infection

Risks of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement are:

- Blood clot or bleeding in the brain

- Brain swelling

- Hole in the intestines (bowel perforation), which can occur later after surgery

- Leakage of CSF under the skin

- Infection of the shunt, brain, or in the abdomen

- Damage to brain tissue

- Seizures

The shunt may stop working. If this happens, fluid will begin to build up in the brain again. As a child grows, the shunt may need to be repositioned.

Before the Procedure

Tell your surgeon or nurse if:

- You are or could be pregnant

- You are taking any medicines, including drugs, supplements, or herbs you bought without a prescription

Planning for your surgery:

- If you have diabetes, heart disease, or other medical conditions, your surgeon may ask you to see the provider who treats you for these conditions.

- If you smoke, it's important to cut back or quit. Smoking can slow healing and increase the risk for blood clots. Ask your provider for help quitting smoking.

- If needed, prepare your home to make it easier to recover after surgery.

- Ask your surgeon if you need to arrange to have someone drive you home after your surgery.

During the week before your surgery:

- You may be asked to temporarily stop taking medicines that keep your blood from clotting. These medicines are called blood thinners. This includes over-the-counter medicines and supplements such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn), and vitamin E. Many prescription medicines are also blood thinners.

- Ask your surgeon which medicines you should still take on the day of surgery.

- Let your surgeon know about any illness you may have before your surgery. This includes COVID-19, a cold, flu, fever, herpes breakout, or other illness. If you do get sick, your surgery may need to be postponed.

On the day of surgery:

- Follow instructions about when to stop eating and drinking.

- Take the medicines your surgeon told you to take with a small sip of water.

- Follow instructions on when to arrive at the hospital. Be sure to arrive on time.

- Follow any other instructions about preparing at home. This may include bathing with a special soap.

After the Procedure

The person may need to lie flat for 24 hours the first time a shunt is placed.

How long the hospital stay is depends on the reason the shunt is needed. The health care team will closely monitor the person. Intravenous (IV) fluids, antibiotics, and pain medicines will be given if needed.

Follow the surgeon's instructions about how to take care of the shunt at home. This may include taking medicine to prevent infection of the shunt.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Shunt placement is usually successful in reducing pressure in the brain. But if hydrocephalus is related to other conditions, such as spina bifida, brain tumor, meningitis, encephalitis, or hemorrhage, these conditions could affect the prognosis. How severe hydrocephalus is before surgery also affects the outcome.

References

Badhiwala JH, Kulkarni AV. Ventricular shunting procedures. In: Winn HR, ed. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 227.

Rosenberg GA. Brain edema and disorders of cerebrospinal fluid circulation. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 88.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 12/31/2023

Reviewed by: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.