Aging changes in the bones - muscles - joints

Osteoporosis and aging; Muscle weakness associated with aging; Osteoarthritis

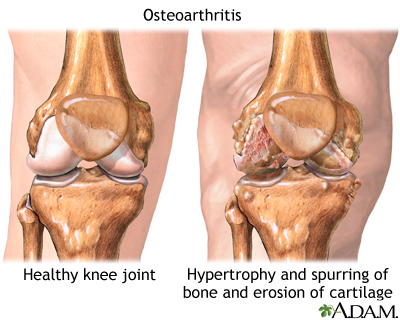

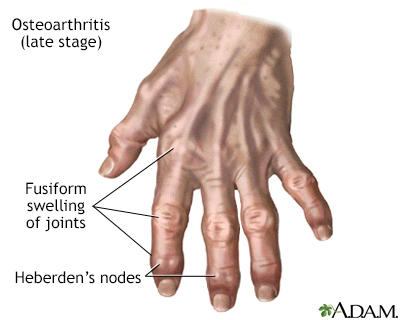

Osteoarthritis is a chronic disease of the joint cartilage and bone, often thought to result from wear and tear on a joint, although there are other causes such as congenital defects, trauma and metabolic disorders. Joints appear larger, are stiff and painful and usually feel worse the more they are used throughout the day.

Osteoarthritis is associated with the aging process and can affect any joint. The cartilage of the affected joint is gradually worn down, eventually causing bone to rub against bone. Bony spurs develop on the unprotected bones causing pain and inflammation.

Osteoporosis is a condition characterized by progressive loss of bone density, thinning of bone tissue and increased vulnerability to fractures. Osteoporosis may result from disease, dietary or hormonal deficiency or advanced age. Regular exercise and vitamin and mineral supplements can reduce and even reverse loss of bone density.

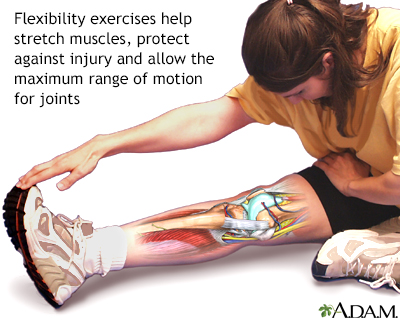

Flexibility exercise in its simplest form stretches and elongates muscles. Disciplines which incorporate stretching with breath control and meditation include yoga and tai chi. The benefits of greater flexibility may go beyond the physical to the improvement of stress reduction and the promotion of a greater sense of well-being.

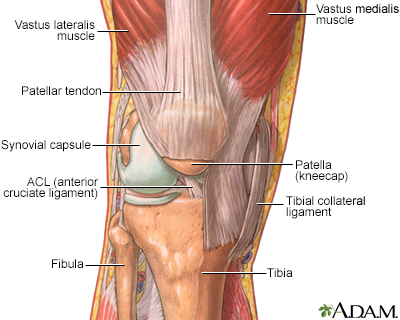

Joints, particularly hinge joints like the elbow and the knee, are complex structures made up of bone, muscles, synovium, cartilage, and ligaments that are designed to bear weight and move the body through space. The knee consists of the femur (thigh bone) above, and the tibia (shin bone) and fibula below. The kneecap (patella) glides through a shallow groove on the front part of the lower thigh bone. Ligaments and tendons connect the three bones of the knee, which are contained in the joint capsule (synovium) and are cushioned by cartilage.

Information

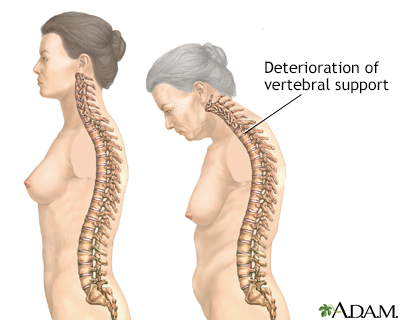

Changes in posture and gait (walking pattern) are common with aging.

The skeleton provides support and structure to the body. Joints are the areas where bones come together. They allow the skeleton to be flexible for movement. In a joint, bones do not directly contact each other. Instead, they are cushioned by cartilage in the joint, synovial membranes around the joint, and fluid.

Muscles provide the force and strength to move the body. Coordination is directed by the brain, but is affected by changes in the muscles and joints. Changes in the muscles, joints, and bones affect the posture and walk, and lead to weakness and slowed movement.

AGING CHANGES

People lose bone mass or density as they age, especially women after menopause. The bones lose calcium and other minerals.

The spine is made up of bones called vertebrae. Between each bone is a gel-like cushion (called a disk). With aging, the middle of the body (trunk) becomes shorter as the disks gradually lose fluid and become thinner.

Vertebrae also lose some of their mineral content, making each bone thinner. The spinal column becomes curved and compressed (packed together). Bone spurs caused by aging and overall use of the spine may also form on the vertebrae.

The foot arches become less pronounced, contributing to a slight loss of height.

The long bones of the arms and legs are more brittle because of mineral loss, but they do not change length. This makes the arms and legs look longer when compared with the shortened trunk.

The joints become stiffer and less flexible. Fluid in the joints may decrease. The cartilage may begin to rub together and wear away. Minerals may deposit in and around some joints (calcification). This is common around the shoulder.

Hip and knee joints may begin to lose cartilage (degenerative changes). The finger joints lose cartilage and the bones thicken slightly. Finger joint changes, most often bony swelling called osteophytes, are more common in women. These changes may be inherited.

Lean body mass decreases. This decrease is partly caused by a loss of muscle tissue (atrophy). The speed and amount of muscle changes seem to be caused by genes. Muscle changes often begin in the 20s in men and in the 40s in women.

Lipofuscin (an age-related pigment) and fat are deposited in muscle tissue. The muscle fibers shrink. Muscle tissue is replaced more slowly. Lost muscle tissue may be replaced with a tough fibrous tissue. This is most noticeable in the hands, which may look thin and bony.

Muscles are less toned and less able to contract because of changes in the muscle tissue and normal aging changes in the nervous system. Muscles may become rigid with age and may lose tone, even with regular exercise.

EFFECT OF CHANGES

Bones become more brittle and may break more easily. Overall height decreases, mainly because the trunk and spine shorten.

Breakdown of the joints may lead to inflammation, pain, stiffness, and deformity. Joint changes affect almost all older people. These changes range from minor stiffness to severe arthritis.

The posture may become more stooped (bent). The knees and hips may become more flexed. The neck may tilt, and the shoulders may narrow while the pelvis becomes wider.

Movement slows and may become limited. The walking pattern (gait) becomes slower and shorter. Walking may become unsteady, and there is less arm swinging. Older people get tired more easily and have less energy.

Strength and endurance change. Loss of muscle mass reduces strength.

COMMON PROBLEMS

Osteoporosis is a common problem, especially for older women. Bones break more easily. Compression fractures of the vertebrae can cause pain and reduce mobility.

Muscle weakness contributes to fatigue, weakness, and reduced activity tolerance. Joint problems ranging from mild stiffness to debilitating arthritis (osteoarthritis) are very common.

The risk of injury increases because gait changes, instability, and loss of balance may lead to falls.

Some older people have reduced reflexes. This is most often caused by changes in the muscles and tendons, rather than changes in the nerves. Decreased knee jerk or ankle jerk reflexes can occur. Some changes, such as a positive Babinski reflex, are not a normal part of aging.

Involuntary movements (muscle tremors and fine movements called fasciculations) are more common in the older people. Older people who are not active may have weakness or abnormal sensations (paresthesias).

People who are unable to move on their own, or who do not stretch their muscles with exercise, may get muscle contractures.

PREVENTION

Exercise is one of the best ways to slow or prevent problems with the muscles, joints, and bones. A moderate exercise program can help you maintain strength, balance, and flexibility. Exercise helps the bones stay strong.

Talk to your health care provider before starting a new exercise program.

It is important to eat a well-balanced diet with plenty of calcium. Women need to be particularly careful to get enough calcium and vitamin D as they age. Postmenopausal women and men over age 70 should take in 1,200 mg of calcium per day. Women and men over age 70 should get 800 international units (IU) of vitamin D daily. If you have osteoporosis, talk to your provider about prescription treatments.

RELATED TOPICS

References

Di Cesare PE, Haudenschild DR, Abramson SB, Samuels J. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. In:Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, Koretzky GA, McInnes IB, O'Dell JR, eds. Firestein & Kelley's Textbook ofRheumatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 104.

Gregson CL. Bone and joint aging. In: Fillit HM, Rockwood K, Young J, eds. Brocklehurst'sTextbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 20.

US Department of Health & Human Services. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements website. Vitamin D: fact sheet for health professionals.

Walston JD. Common clinical sequelae of aging. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 24.

Weber TJ. Osteoporosis. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 225.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 7/15/2024

Reviewed by: Frank D. Brodkey, MD, FCCM, Associate Professor, Section of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. Editorial update 01/07/2025.