Corneal transplant

Keratoplasty; Penetrating keratoplasty; Lamellar keratoplasty; Keratoconus - corneal transplant; Fuchs' dystrophy - corneal transplant

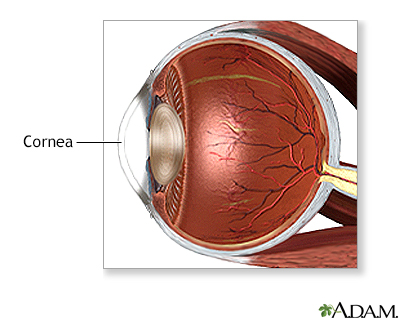

The cornea is the clear outer lens on the front of the eye. A corneal transplant is surgery to replace the cornea with tissue from a donor. It is one of the most common transplants done.

Corneal surgery involves replacing the clear covering of the eye (cornea). The surgery is recommended for severe corneal infection, injury, scarring, and for corneas that no longer allow light to pass through. The outcome for corneal surgery is usually very good and transplanted corneas have a long life expectancy.

The cornea is the clear covering of the eye over the colored iris and the pupil.

Description

You will most likely be awake during the transplant. You will get medicine to relax you. Local anesthesia (numbing medicine) will be injected around your eye to block pain and prevent eye movement during the surgery.

The tissue for your corneal transplant will come from a person (donor) who has recently died. The donated cornea is processed and tested by a local eye bank to make sure it is safe for use in your surgery.

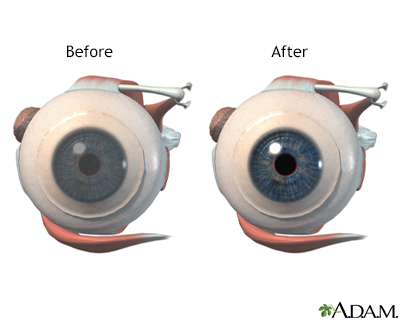

For years, the most common type of corneal transplant was called penetrating keratoplasty.

- It is still a frequently performed operation.

- During this procedure, your surgeon will remove a small round piece of your cornea.

- The donated tissue will then be sewn into the opening of your cornea.

A newer technique is called lamellar keratoplasty.

- In this procedure, only the inner or outer layers of the cornea are replaced, rather than all the layers, as in penetrating keratoplasty.

- There are several different lamellar techniques. They differ mostly on which layer is replaced and how the donor tissue is prepared.

- All lamellar procedures lead to faster recovery and fewer complications.

Why the Procedure Is Performed

A corneal transplant is recommended for people who have:

- Vision problems caused by thinning of the cornea, most often due to keratoconus. (A transplant may be considered when less invasive treatments are not an option.)

- Scarring of the cornea from severe infections or injuries

- Vision loss caused by cloudiness of the cornea, most often due to Fuchs dystrophy

Risks

The body may reject the transplanted tissue. This occurs in about 1 out of 3 patients in the first 5 years. Rejection can sometimes be controlled with steroid eye drops. There have rare cases of graft rejection reported soon after COVID-19 vaccination.

Other risks for a corneal transplant are:

Before the Procedure

Tell your surgeon and health care provider about any medical conditions you may have, including allergies. Also tell your provider what medicines you are taking, even medicines, supplements, and herbs you bought without a prescription.

You may need to limit medicines that make it hard for your blood to clot (blood thinners) for 10 days before the surgery. Some of these are aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and warfarin (Coumadin).

Ask your surgeon which of your other daily medicines, such as water pills, insulin or pills for diabetes, you should take on the morning of your surgery.

You will need to stop eating and drinking most fluids after midnight the night before your surgery. Most surgeons will let you have water, apple juice, and plain coffee or tea (without cream or sugar) up to 2 hours before surgery. Do not drink alcohol 24 hours before or after surgery.

On the day of your surgery, wear loose, comfortable clothing. Do not wear any jewelry. Do not put creams, lotions, or makeup on your face or around your eyes.

You will need to have someone drive you home after your surgery.

Note: These are general guidelines. Your surgeon may give you other instructions.

After the Procedure

You will go home on the same day as your surgery. Your surgeon will give you an eye patch to wear for about 1 to 4 days.

Your surgeon will prescribe eye drops to help your eye heal and prevent infection and rejection.

Your surgeon will remove the stitches at a follow-up visit. Some stitches may stay in place for as long as a year, or they might not be removed at all.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Full recovery of eyesight may take up to a year. This is because it takes time for the swelling to go down. Most people who have a successful corneal transplant will have good vision for many years. If you have other eye problems, you may still have vision loss from those conditions.

You may need glasses or contact lenses to achieve the best vision. Laser vision correction may be an option if you have nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism after the transplant has fully healed.

References

Cioffi GA, Liebmann JM. Diseases of the visual system. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 391.

Gómez-Benlloch A,, Montesel A, Pareja-Aricò L, et al. Causes of corneal transplant failure: a multicentric study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99(6):e922-e928. PMID: 33421330

Hagem AM, Thorsrud A, Sæthre M, Sandvik G, Kristianslund O, Drolsum L. Dramatic reduction in corneal transplants for keratoconus 15 Years after the introduction of corneal collagen crosslinking. Cornea. 2024;43(4):437-442. PMID: 37851565

McTiernan CD, Simpson FC, Haagdorens M, et al. LiQD cornea: pro-regeneration collagen mimetics as patches and alternatives to corneal transplantation. Science Advances. 2020;6(25):eaba2187 PMID: 32917640

Mousavi M, Kahuam-López N, Iovieno A, Yeung SN. Global impact of COVID-19 on corneal donor tissue harvesting and corneal transplantation. Front Med (Lausanne).2023;10:1210293. PMID: 37608828

Phylactou M, Li JO, Larkin DFP. Characteristics of endothelial corneal transplant rejection following immunisation with SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccine. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(7):893-896. PMID: 33910885

Pierson KL, Holland EJ, Mannis MJ. Corneal transplantation in ocular surface disease. In: Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 170.

Venkateswaran N, Nikpoor N, Perez VL. Surgical ocular surface reconstruction. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 4.33.

Version Info

Last reviewed on: 8/5/2024

Reviewed by: Franklin W. Lusby, MD, Ophthalmologist, Lusby Vision Institute, La Jolla, CA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.